Combinatorics

Combinatorics is the art of counting. It deals with selections, arrangements, and combinations of objects. Questions involve determining the number of ways to perform tasks, arrange items (permutations), or choose subsets (combinations), often using principles like the product rule and sum rule.

Pigeonhole Principle Double Counting Binomial Coefficients and Pascal's Triangle Product Rule / Rule of Product Graph Theory Matchings Induction (Mathematical Induction) Game Theory Combinatorial Geometry Invariants Case Analysis / Checking Cases Processes / Procedures Number Tables Colorings-

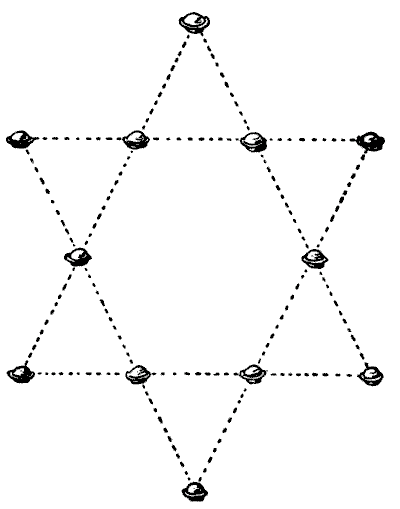

THE TWELVE MINCE-PIES

It will be seen in our illustration how twelve mince-pies may be placed on the table so as to form six straight rows with four pies in every row. The puzzle is to remove only four of them to new positions so that there shall be seven straight rows with four in every row. Which four would you remove, and where would you replace them? Sources:

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 211

-

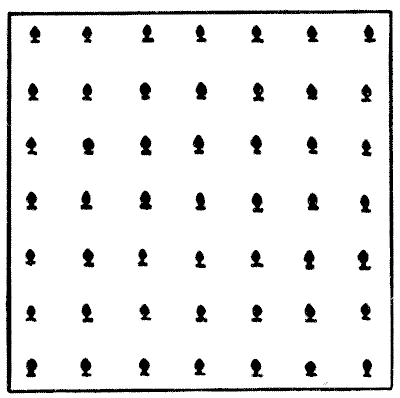

THE BURMESE PLANTATION

A short time ago I received an interesting communication from the British chaplain at Meiktila, Upper Burma, in which my correspondent informed me that he had found some amusement on board ship on his way out in trying to solve this little poser.

If he has a plantation of forty-nine trees, planted in the form of a square as shown in the accompanying illustration, he wishes to know how he may cut down twenty-seven of the trees so that the twenty-two left standing shall form as many rows as possible with four trees in every row.

Of course there may not be more than four trees in any row.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 212

-

TURKS AND RUSSI

This puzzle is on the lines of the Afridi problem published by me in Tit-Bits some years ago.

On an open level tract of country a party of Russian infantry, no two of whom were stationed at the same spot, were suddenly surprised by thirty-two Turks, who opened fire on the Russians from all directions. Each of the Turks simultaneously fired a bullet, and each bullet passed immediately over the heads of three Russian soldiers. As each of these bullets when fired killed a different man, the puzzle is to discover what is the smallest possible number of soldiers of which the Russian party could have consisted and what were the casualties on each side.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 213

-

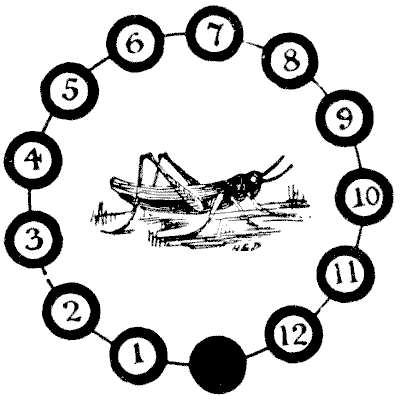

THE GRASSHOPPER PUZZLE

It has been suggested that this puzzle was a great favourite among the young apprentices of the City of London in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Readers will have noticed the curious brass grasshopper on the Royal Exchange. This long-lived creature escaped the fires of `1666` and `1838`. The grasshopper, after his kind, was the crest of Sir Thomas Gresham, merchant grocer, who died in `1579`, and from this cause it has been used as a sign by grocers in general. Unfortunately for the legend as to its origin, the puzzle was only produced by myself so late as the year `1900`. On twelve of the thirteen black discs are placed numbered counters or grasshoppers. The puzzle is to reverse their order, so that they shall read, `1, 2, 3, 4`, etc., in the opposite direction, with the vacant disc left in the same position as at present. Move one at a time in any order, either to the adjoining vacant disc or by jumping over one grasshopper, like the moves in draughts. The moves or leaps may be made in either direction that is at any time possible. What are the fewest possible moves in which it can be done? Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures

Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 215

-

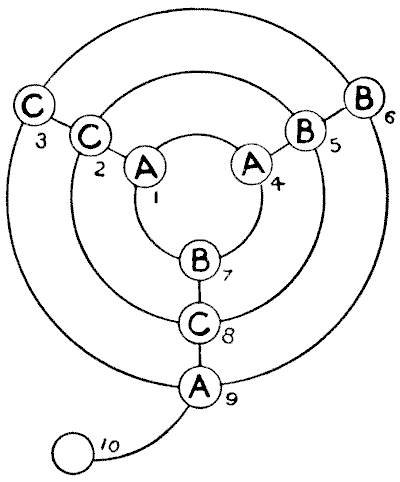

A RAILWAY PUZZLE

Make a diagram, on a large sheet of paper, like the illustration, and have three counters marked A, three marked B, and three marked C. It will be seen that at the intersection of lines there are nine stopping-places, and a tenth stopping-place is attached to the outer circle like the tail of a Q. Place the three counters or engines marked A, the three marked B, and the three marked C at the places indicated. The puzzle is to move the engines, one at a time, along the lines, from stopping-place to stopping-place, until you succeed in getting an A, a B, and a C on each circle, and also A, B, and C on each straight line. You are required to do this in as few moves as possible. How many moves do you need?

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory

Make a diagram, on a large sheet of paper, like the illustration, and have three counters marked A, three marked B, and three marked C. It will be seen that at the intersection of lines there are nine stopping-places, and a tenth stopping-place is attached to the outer circle like the tail of a Q. Place the three counters or engines marked A, the three marked B, and the three marked C at the places indicated. The puzzle is to move the engines, one at a time, along the lines, from stopping-place to stopping-place, until you succeed in getting an A, a B, and a C on each circle, and also A, B, and C on each straight line. You are required to do this in as few moves as possible. How many moves do you need?

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 222

-

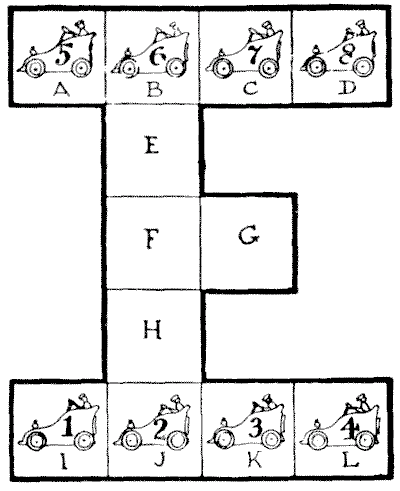

THE MOTOR-GARAGE PUZZLE

The difficulties of the proprietor of a motor garage are converted into a little pastime of a kind that has a peculiar fascination. All you need is to make a simple plan or diagram on a sheet of paper or cardboard and number eight counters, `1` to `8`. Then a whole family can enter into an amusing competition to find the best possible solution of the difficulty.

The illustration represents the plan of a motor garage, with accommodation for twelve cars. But the premises are so inconveniently restricted that the proprietor is often caused considerable perplexity. Suppose, for example, that the eight cars numbered `1` to `8` are in the positions shown, how are they to be shifted in the quickest possible way so that `1, 2, 3`, and `4` shall change places with `5, 6, 7`, and `8`—that is, with the numbers still running from left to right, as at present, but the top row exchanged with the bottom row? What are the fewest possible moves?

One car moves at a time, and any distance counts as one move. To prevent misunderstanding, the stopping-places are marked in squares, and only one car can be in a square at the same time.

Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 224

-

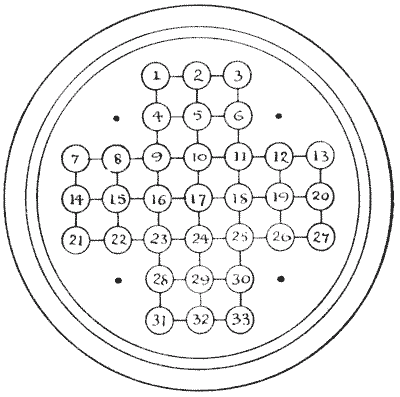

CENTRAL SOLITAIRE

This ancient puzzle was a great favourite with our grandmothers, and most of us, I imagine, have on occasions come across a "Solitaire" board—a round polished board with holes cut in it in a geometrical pattern, and a glass marble in every hole. Sometimes I have noticed one on a side table in a suburban front parlour, or found one on a shelf in a country cottage, or had one brought under my notice at a wayside inn. Sometimes they are of the form shown above, but it is equally common for the board to have four more holes, at the points indicated by dots. I select the simpler form.

Though "Solitaire" boards are still sold at the toy shops, it will be sufficient if the reader will make an enlarged copy of the above on a sheet of cardboard or paper, number the "holes," and provide himself with `33` counters, buttons, or beans. Now place a counter in every hole except the central one, No. `17`, and the puzzle is to take off all the counters in a series of jumps, except the last counter, which must be left in that central hole. You are allowed to jump one counter over the next one to a vacant hole beyond, just as in the game of draughts, and the counter jumped over is immediately taken off the board. Only remember every move must be a jump; consequently you will take off a counter at each move, and thirty-one single jumps will of course remove all the thirty-one counters. But compound moves are allowed (as in draughts, again), for so long as one counter continues to jump, the jumps all count as one move.

Here is the beginning of an imaginary solution which will serve to make the manner of moving perfectly plain, and show how the solver should write out his attempts: `5-17`, `12-10`, `26-12`, `24-26` (`13-11`, `11-25`), `9-11` (`26-24`, `24-10`, `10-12`), etc., etc. The jumps contained within brackets count as one move, because they are made with the same counter. Find the fewest possible moves. Of course, no diagonal jumps are permitted; you can only jump in the direction of the lines.

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 227

-

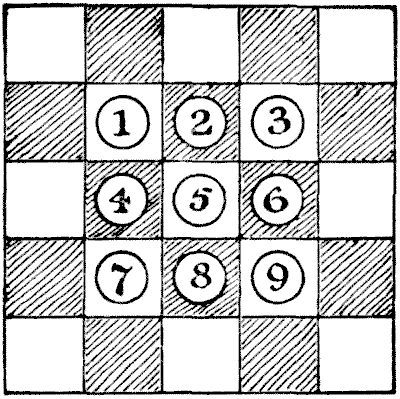

THE NINE ALMONDS

"Here is a little puzzle," said a Parson, "that I have found peculiarly fascinating. It is so simple, and yet it keeps you interested indefinitely."

The reverend gentleman took a sheet of paper and divided it off into twenty-five squares, like a square portion of a chessboard. Then he placed nine almonds on the central squares, as shown in the illustration, where we have represented numbered counters for convenience in giving the solution.

"Now, the puzzle is," continued the Parson, "to remove eight of the almonds and leave the ninth in the central square. You make the removals by jumping one almond over another to the vacant square beyond and taking off the one jumped over—just as in draughts, only here you can jump in any direction, and not diagonally only. The point is to do the thing in the fewest possible moves."

The following specimen attempt will make everything clear. Jump `4` over `1, 5` over `9, 3` over `6, 5` over `3, 7` over `5` and `2, 4` over `7, 8` over `4`. But `8` is not left in the central square, as it should be. Remember to remove those you jump over. Any number of jumps in succession with the same almond count as one move.

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 229

-

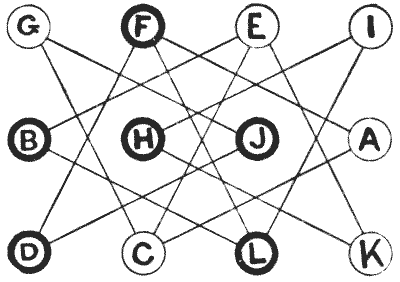

THE EXCHANGE PUZZLE

Here is a rather entertaining little puzzle with moving counters. You only need twelve counters—six of one colour, marked A, C, E, G, I, and K, and the other six marked B, D, F, H, J, and L. You first place them on the diagram, as shown in the illustration, and the puzzle is to get them into regular alphabetical order, as follows:—

A B C D E F G H I J K L The moves are made by exchanges of opposite colours standing on the same line. Thus, G and J may exchange places, or F and A, but you cannot exchange G and C, or F and D, because in one case they are both white and in the other case both black. Can you bring about the required arrangement in seventeen exchanges?

It cannot be done in fewer moves. The puzzle is really much easier than it looks, if properly attacked.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Invariants Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 234

-

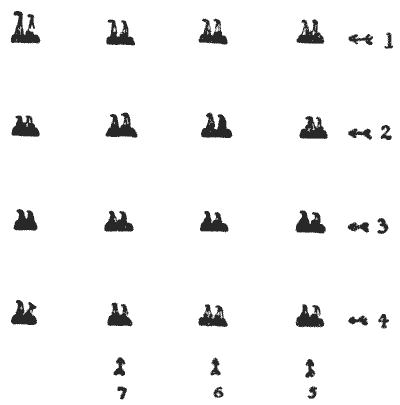

TORPEDO PRACTICE

If a fleet of sixteen men-of-war were lying at anchor and surrounded by the enemy, how many ships might be sunk if every torpedo, projected in a straight line, passed under three vessels and sank the fourth? In the diagram we have arranged the fleet in square formation, where it will be seen that as many as seven ships may be sunk (those in the top row and first column) by firing the torpedoes indicated by arrows. Anchoring the fleet as we like, to what extent can we increase this number? Remember that each successive ship is sunk before another torpedo is launched, and that every torpedo proceeds in a different direction; otherwise, by placing the ships in a straight line, we might sink as many as thirteen! It is an interesting little study in naval warfare, and eminently practical—provided the enemy will allow you to arrange his fleet for your convenience and promise to lie still and do nothing!

Sources:

If a fleet of sixteen men-of-war were lying at anchor and surrounded by the enemy, how many ships might be sunk if every torpedo, projected in a straight line, passed under three vessels and sank the fourth? In the diagram we have arranged the fleet in square formation, where it will be seen that as many as seven ships may be sunk (those in the top row and first column) by firing the torpedoes indicated by arrows. Anchoring the fleet as we like, to what extent can we increase this number? Remember that each successive ship is sunk before another torpedo is launched, and that every torpedo proceeds in a different direction; otherwise, by placing the ships in a straight line, we might sink as many as thirteen! It is an interesting little study in naval warfare, and eminently practical—provided the enemy will allow you to arrange his fleet for your convenience and promise to lie still and do nothing!

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 235