Combinatorics

Combinatorics is the art of counting. It deals with selections, arrangements, and combinations of objects. Questions involve determining the number of ways to perform tasks, arrange items (permutations), or choose subsets (combinations), often using principles like the product rule and sum rule.

Pigeonhole Principle Double Counting Binomial Coefficients and Pascal's Triangle Product Rule / Rule of Product Graph Theory Matchings Induction (Mathematical Induction) Game Theory Combinatorial Geometry Invariants Case Analysis / Checking Cases Processes / Procedures Number Tables Colorings-

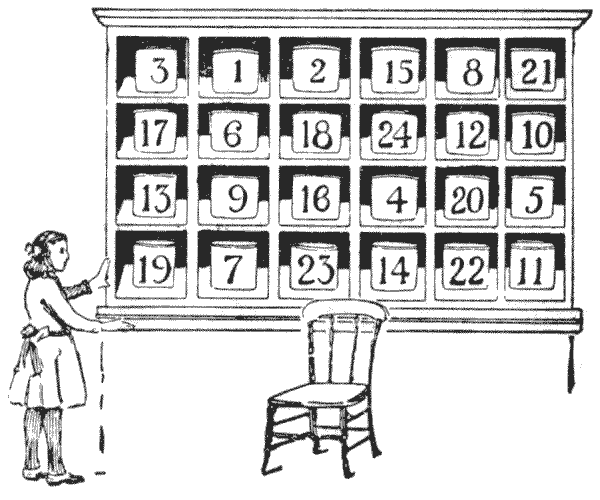

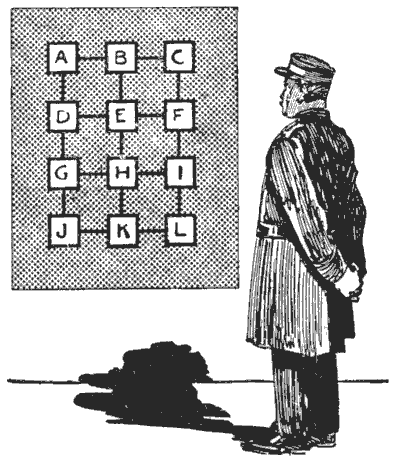

ARRANGING THE JAMPOTS

I happened to see a little girl sorting out some jam in a cupboard for her mother. She was putting each different kind of preserve apart on the shelves. I noticed that she took a pot of damson in one hand and a pot of gooseberry in the other and made them change places; then she changed a strawberry with a raspberry, and so on. It was interesting to observe what a lot of unnecessary trouble she gave herself by making more interchanges than there was any need for, and I thought it would work into a good puzzle.

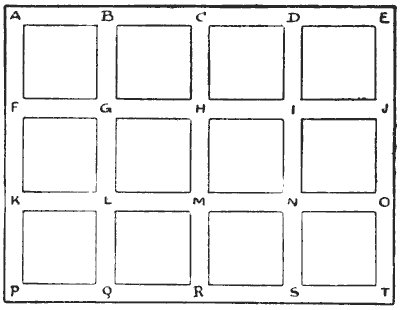

It will be seen in the illustration that little Dorothy has to manipulate twenty-four large jampots in as many pigeon-holes. She wants to get them in correct numerical order—that is, `1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6` on the top shelf, `7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12` on the next shelf, and so on. Now, if she always takes one pot in the right hand and another in the left and makes them change places, how many of these interchanges will be necessary to get all the jampots in proper order? She would naturally first change the `1` and the `3`, then the `2` and the `3`, when she would have the first three pots in their places. How would you advise her to go on then? Place some numbered counters on a sheet of paper divided into squares for the pigeon-holes, and you will find it an amusing puzzle.

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 238

-

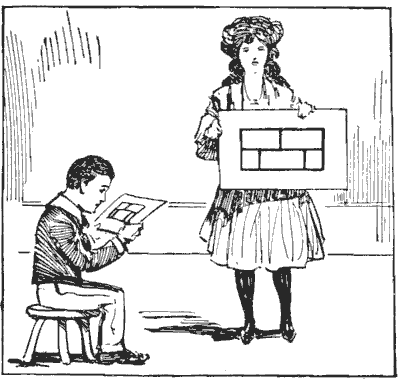

A JUVENILE PUZZLE

For years I have been perpetually consulted by my juvenile friends about this little puzzle. Most children seem to know it, and yet, curiously enough, they are invariably unacquainted with the answer. The question they always ask is, "Do, please, tell me whether it is really possible." I believe Houdin the conjurer used to be very fond of giving it to his child friends, but I cannot say whether he invented the little puzzle or not. No doubt a large number of my readers will be glad to have the mystery of the solution cleared up, so I make no apology for introducing this old "teaser."

The puzzle is to draw with three strokes of the pencil the diagram that the little girl is exhibiting in the illustration. Of course, you must not remove your pencil from the paper during a stroke or go over the same line a second time. You will find that you can get in a good deal of the figure with one continuous stroke, but it will always appear as if four strokes are necessary.

Another form of the puzzle is to draw the diagram on a slate and then rub it out in three rubs.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 239

-

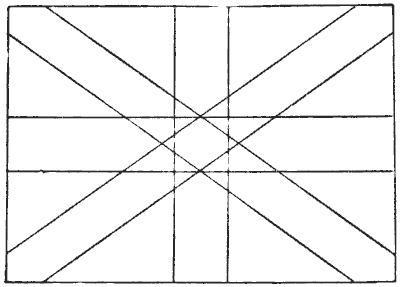

THE UNION JACK

The illustration is a rough sketch somewhat resembling the British flag, the Union Jack. It is not possible to draw the whole of it without lifting the pencil from the paper or going over the same line twice. The puzzle is to find out just how much of the drawing it is possible to make without lifting your pencil or going twice over the same line. Take your pencil and see what is the best you can do.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory

The illustration is a rough sketch somewhat resembling the British flag, the Union Jack. It is not possible to draw the whole of it without lifting the pencil from the paper or going over the same line twice. The puzzle is to find out just how much of the drawing it is possible to make without lifting your pencil or going twice over the same line. Take your pencil and see what is the best you can do.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 240

-

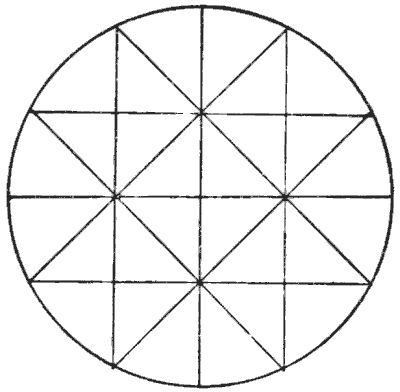

THE DISSECTED CIRCLE

How many continuous strokes, without lifting your pencil from the paper, do you require to draw the design shown in our illustration? Directly you change the direction of your pencil it begins a new stroke. You may go over the same line more than once if you like. It requires just a little care, or you may find yourself beaten by one stroke. Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 241

-

THE TUBE INSPECTOR'S PUZZLE

The man in our illustration is in a little dilemma. He has just been appointed inspector of a certain system of tube railways, and it is his duty to inspect regularly, within a stated period, all the company's seventeen lines connecting twelve stations, as shown on the big poster plan that he is contemplating. Now he wants to arrange his route so that it shall take him over all the lines with as little travelling as possible. He may begin where he likes and end where he likes. What is his shortest route?

Could anything be simpler? But the reader will soon find that, however he decides to proceed, the inspector must go over some of the lines more than once. In other words, if we say that the stations are a mile apart, he will have to travel more than seventeen miles to inspect every line. There is the little difficulty. How far is he compelled to travel, and which route do you recommend?

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 242

-

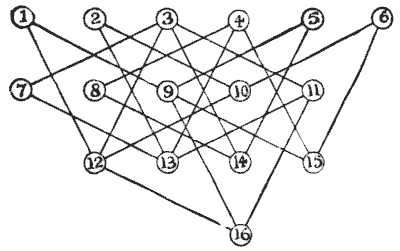

VISITING THE TOWNS

A traveller, starting from town No. `1`, wishes to visit every one of the towns once, and once only, going only by roads indicated by straight lines. How many different routes are there from which he can select? Of course, he must end his journey at No. `1`, from which he started, and must take no notice of cross roads, but go straight from town to town. This is an absurdly easy puzzle, if you go the right way to work.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory

A traveller, starting from town No. `1`, wishes to visit every one of the towns once, and once only, going only by roads indicated by straight lines. How many different routes are there from which he can select? Of course, he must end his journey at No. `1`, from which he started, and must take no notice of cross roads, but go straight from town to town. This is an absurdly easy puzzle, if you go the right way to work.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 243

-

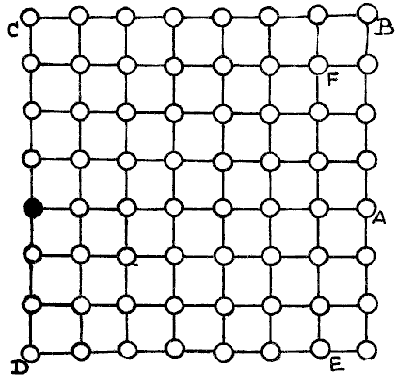

THE FIFTEEN TURNINGS

Here is another queer travelling puzzle, the solution of which calls for ingenuity. In this case the traveller starts from the black town and wishes to go as far as possible while making only fifteen turnings and never going along the same road twice. The towns are supposed to be a mile apart. Supposing, for example, that he went straight to A, then straight to B, then to C, D, E, and F, you will then find that he has travelled thirty-seven miles in five turnings. Now, how far can he go in fifteen turnings? Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 244

-

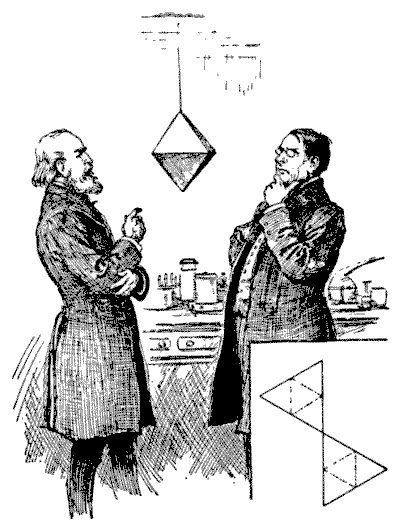

THE FLY ON THE OCTAHEDRON

"Look here," said the professor to his colleague, "I have been watching that fly on the octahedron, and it confines its walks entirely to the edges. What can be its reason for avoiding the sides?"

"Perhaps it is trying to solve some route problem," suggested the other. "Supposing it to start from the top point, how many different routes are there by which it may walk over all the edges, without ever going twice along the same edge in any route?"

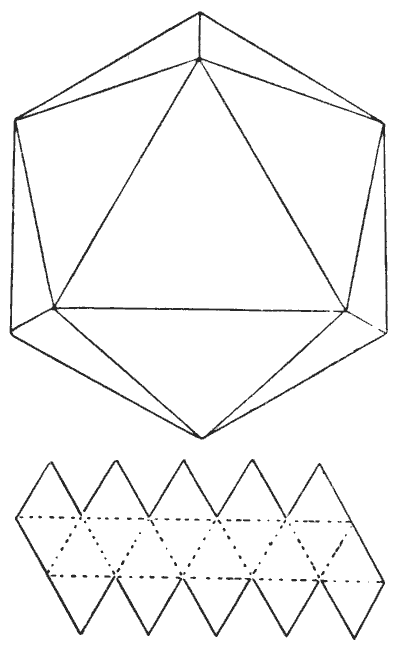

The problem was a harder one than they expected, and after working at it during leisure moments for several days their results did not agree—in fact, they were both wrong. If the reader is surprised at their failure, let him attempt the little puzzle himself. I will just explain that the octahedron is one of the five regular, or Platonic, bodies, and is contained under eight equal and equilateral triangles. If you cut out the two pieces of cardboard of the shape shown in the margin of the illustration, cut half through along the dotted lines and then bend them and put them together, you will have a perfect octahedron. In any route over all the edges it will be found that the fly must end at the point of departure at the top.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space -> Polyhedra -> Regular Polyhedra- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 245

-

THE ICOSAHEDRON PUZZLE

The icosahedron is another of the five regular, or Platonic, bodies having all their sides, angles, and planes similar and equal. It is bounded by twenty similar equilateral triangles. If you cut out a piece of cardboard of the form shown in the smaller diagram, and cut half through along the dotted lines, it will fold up and form a perfect icosahedron.

Now, a Platonic body does not mean a heavenly body; but it will suit the purpose of our puzzle if we suppose there to be a habitable planet of this shape. We will also suppose that, owing to a superfluity of water, the only dry land is along the edges, and that the inhabitants have no knowledge of navigation. If every one of those edges is `10,000` miles long and a solitary traveller is placed at the North Pole (the highest point shown), how far will he have to travel before he will have visited every habitable part of the planet—that is, have traversed every one of the edges?

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space -> Polyhedra -> Regular Polyhedra

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space -> Polyhedra -> Regular Polyhedra- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 246

-

INSPECTING A MINE

The diagram is supposed to represent the passages or galleries in a mine. We will assume that every passage, A to B, B to C, C to H, H to I, and so on, is one furlong in length. It will be seen that there are thirty-one of these passages. Now, an official has to inspect all of them, and he descends by the shaft to the point A. How far must he travel, and what route do you recommend? The reader may at first say, "As there are thirty-one passages, each a furlong in length, he will have to travel just thirty-one furlongs." But this is assuming that he need never go along a passage more than once, which is not the case. Take your pencil and try to find the shortest route. You will soon discover that there is room for considerable judgment. In fact, it is a perplexing puzzle. Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 247