Geometry

Geometry is the branch of mathematics concerned with the properties and relations of points, lines, surfaces, solids, and higher dimensional analogues. Expected questions involve calculating lengths, angles, areas, and volumes of various shapes, understanding geometric theorems, and solving problems related to spatial reasoning.

Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space Trigonometry Spherical Geometry Plane Geometry Vectors-

THE CHRISTMAS PUDDING

"Speaking of Christmas puddings," said the host, as he glanced at the imposing delicacy at the other end of the table. "I am reminded of the fact that a friend gave me a new puzzle the other day respecting one. Here it is," he added, diving into his breast pocket.

"'Problem: To find the contents,' I suppose," said the Eton boy.

"No; the proof of that is in the eating. I will read you the conditions."

"'Cut the pudding into two parts, each of exactly the same size and shape, without touching any of the plums. The pudding is to be regarded as a flat disc, not as a sphere.'"

"Why should you regard a Christmas pudding as a disc? And why should any reasonable person ever wish to make such an accurate division?" asked the cynic.

"It is just a puzzle—a problem in dissection." All in turn had a look at the puzzle, but nobody succeeded in solving it. It is a little difficult unless you are acquainted with the principle involved in the making of such puddings, but easy enough when you know how it is done.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Symmetry Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 168

-

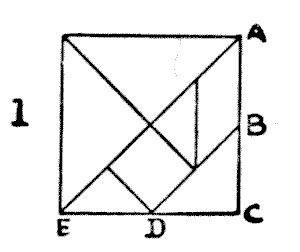

A TANGRAM PARADOX

Many pastimes of great antiquity, such as chess, have so developed and changed down the centuries that their original inventors would scarcely recognize them. This is not the case with Tangrams, a recreation that appears to be at least four thousand years old, that has apparently never been dormant, and that has not been altered or "improved upon" since the legendary Chinaman Tan first cut out the seven pieces shown in Diagram I. If you mark the point B, midway between A and C, on one side of a square of any size, and D, midway between C and E, on an adjoining side, the direction of the cuts is too obvious to need further explanation. Every design in this article is built up from the seven pieces of blackened cardboard. It will at once be understood that the possible combinations are infinite.

The late Mr. Sam Loyd, of New York, who published a small book of very ingenious designs, possessed the manuscripts of the late Mr. Challenor, who made a long and close study of Tangrams. This gentleman, it is said, records that there were originally seven books of Tangrams, compiled in China two thousand years before the Christian era. These books are so rare that, after forty years' residence in the country, he only succeeded in seeing perfect copies of the first and seventh volumes with fragments of the second. Portions of one of the books, printed in gold leaf upon parchment, were found in Peking by an English soldier and sold for three hundred pounds.

A few years ago a little book came into my possession, from the library of the late Lewis Carroll, entitled The Fashionable Chinese Puzzle. It contains three hundred and twenty-three Tangram designs, mostly nondescript geometrical figures, to be constructed from the seven pieces. It was "Published by J. and E. Wallis, `42` Skinner Street, and J. Wallis, Jun., Marine Library, Sidmouth" (South Devon). There is no date, but the following note fixes the time of publication pretty closely: "This ingenious contrivance has for some time past been the favourite amusement of the ex-Emperor Napoleon, who, being now in a debilitated state and living very retired, passes many hours a day in thus exercising his patience and ingenuity." The reader will find, as did the great exile, that much amusement, not wholly uninstructive, may be derived from forming the designs of others. He will find many of the illustrations to this article quite easy to build up, and some rather difficult. Every picture may thus be regarded as a puzzle.

But it is another pastime altogether to create new and original designs of a pictorial character, and it is surprising what extraordinary scope the Tangrams afford for producing pictures of real life—angular and often grotesque, it is true, but full of character. I give an example of a recumbent figure (`2`) that is particularly graceful, and only needs some slight reduction of its angularities to produce an entirely satisfactory outline.

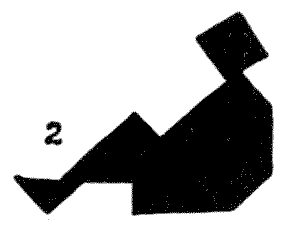

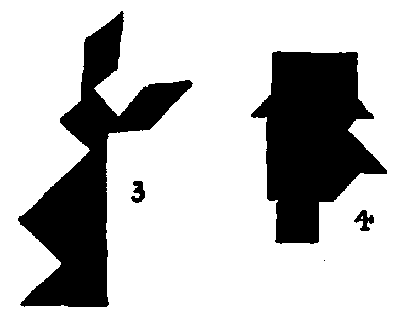

As I have referred to the author of Alice in Wonderland, I give also my designs of the March Hare (`3`) and the Hatter (`4`). I also give an attempt at Napoleon (`5`), and a very excellent Red Indian with his Squaw by Mr. Loyd (`6` and `7`). A large number of other designs will be found in an article by me in The Strand Magazine for November, `1908`.

On the appearance of this magazine article, the late Sir James Murray, the eminent philologist, tried, with that amazing industry that characterized all his work, to trace the word "tangram" to its source. At length he wrote as follows:—"One of my sons is a professor in the Anglo-Chinese college at Tientsin. Through him, his colleagues, and his students, I was able to make inquiries as to the alleged Tan among Chinese scholars. Our Chinese professor here (Oxford) also took an interest in the matter and obtained information from the secretary of the Chinese Legation in London, who is a very eminent representative of the Chinese literati."

"The result has been to show that the man Tan, the god Tan, and the 'Book of Tan' are entirely unknown to Chinese literature, history, or tradition. By most of the learned men the name, or allegation of the existence, of these had never been heard of. The puzzle is, of course, well known. It is called in Chinese ch'i ch'iao t'u; literally, 'seven-ingenious-plan' or 'ingenious-puzzle figure of seven pieces.' No name approaching 'tangram,' or even 'tan,' occurs in Chinese, and the only suggestions for the latter were the Chinese t'an, 'to extend'; or t'ang, Cantonese dialect for 'Chinese.' It was suggested that probably some American or Englishman who knew a little Chinese or Cantonese, wanting a name for the puzzle, might concoct one out of one of these words and the European ending 'gram.' I should say the name 'tangram' was probably invented by an American some little time before `1864` and after `1847`, but I cannot find it in print before the `1864` edition of Webster. I have therefore had to deal very shortly with the word in the dictionary, telling what it is applied to and what conjectures or guesses have been made at the name, and giving a few quotations, one from your own article, which has enabled me to make more of the subject than I could otherwise have done."

Several correspondents have informed me that they possess, or had possessed, specimens of the old Chinese books. An American gentleman writes to me as follows:—"I have in my possession a book made of tissue paper, printed in black (with a Chinese inscription on the front page), containing over three hundred designs, which belongs to the box of 'tangrams,' which I also own. The blocks are seven in number, made of mother-of-pearl, highly polished and finely engraved on either side. These are contained in a rosewood box `2` `1/8` in. square. My great uncle, ——, was one of the first missionaries to visit China. This box and book, along with quite a collection of other relics, were sent to my grandfather and descended to myself."

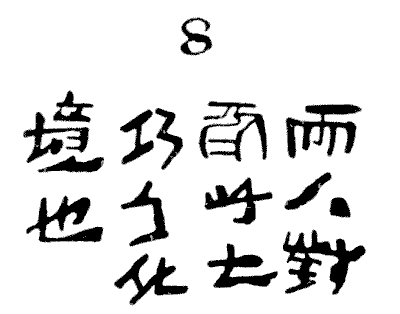

My correspondent kindly supplied me with rubbings of the Tangrams, from which it is clear that they are cut in the exact proportions that I have indicated. I reproduce the Chinese inscription (`8`) for this reason. The owner of the book informs me that he has submitted it to a number of Chinamen in the United States and offered as much as a dollar for a translation. But they all steadfastly refused to read the words, offering the lame excuse that the inscription is Japanese. Natives of Japan, however, insist that it is Chinese. Is there something occult and esoteric about Tangrams, that it is so difficult to lift the veil? Perhaps this page will come under the eye of some reader acquainted with the Chinese language, who will supply the required translation, which may, or may not, throw a little light on this curious question.

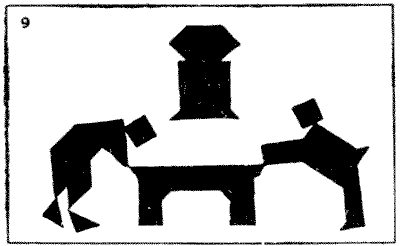

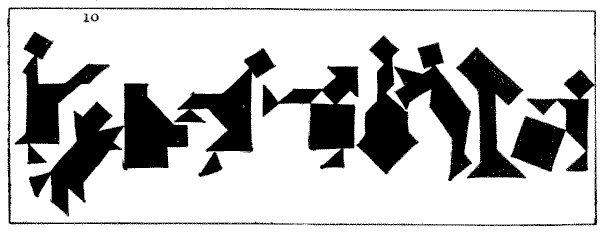

By using several sets of Tangrams at the same time we may construct more ambitious pictures. I was advised by a friend not to send my picture, "A Game of Billiards" (`9`), to the Academy. He assured me that it would not be accepted because the "judges are so hide-bound by convention." Perhaps he was right, and it will be more appreciated by Post-impressionists and Cubists. The players are considering a very delicate stroke at the top of the table. Of course, the two men, the table, and the clock are formed from four sets of Tangrams. My second picture is named "The Orchestra" (`10`), and it was designed for the decoration of a large hall of music. Here we have the conductor, the pianist, the fat little cornet-player, the left-handed player of the double-bass, whose attitude is life-like, though he does stand at an unusual distance from his instrument, and the drummer-boy, with his imposing music-stand. The dog at the back of the pianoforte is not howling: he is an appreciative listener.

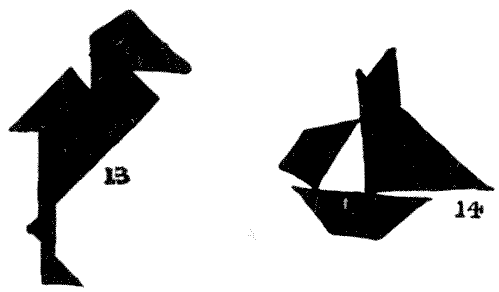

One remarkable thing about these Tangram pictures is that they suggest to the imagination such a lot that is not really there. Who, for example, can look for a few minutes at Lady Belinda (`11`) and the Dutch girl (`12`) without soon feeling the haughty expression in the one case and the arch look in the other? Then look again at the stork (`13`), and see how it is suggested to the mind that the leg is actually much more slender than any one of the pieces employed. It is really an optical illusion. Again, notice in the case of the yacht (`14`) how, by leaving that little angular point at the top, a complete mast is suggested. If you place your Tangrams together on white paper so that they do not quite touch one another, in some cases the effect is improved by the white lines; in other cases it is almost destroyed.

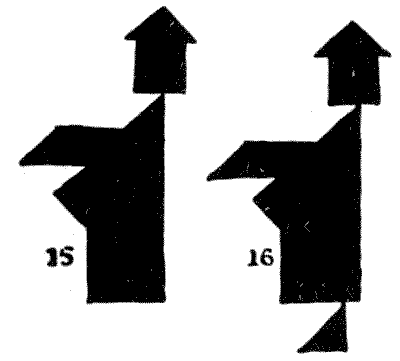

Finally, I give an example from the many curious paradoxes that one happens upon in manipulating Tangrams. I show designs of two dignified individuals (`15` and `16`) who appear to be exactly alike, except for the fact that one has a foot and the other has not. Now, both of these figures are made from the same seven Tangrams. Where does the second man get his foot from?

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 169

-

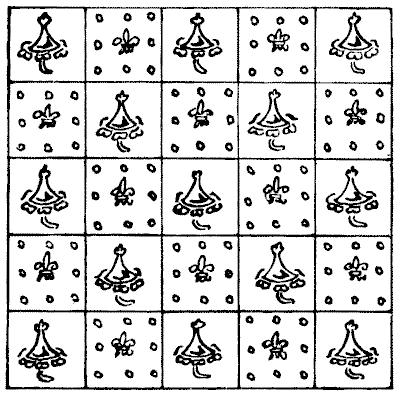

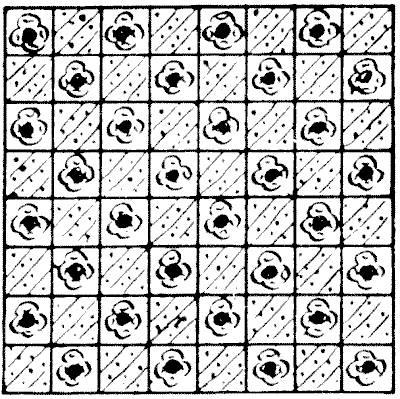

THE CUSHION COVERS

The above represents a square of brocade. A lady wishes to cut it in four pieces so that two pieces will form one perfectly square cushion top, and the remaining two pieces another square cushion top. How is she to do it? Of course, she can only cut along the lines that divide the twenty-five squares, and the pattern must "match" properly without any irregularity whatever in the design of the material. There is only one way of doing it. Can you find it?

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 170

-

THE BANNER PUZZLE

A Lady had a square piece of bunting with two lions on it, of which the illustration is an exactly reproduced reduction. She wished to cut the stuff into pieces that would fit together and form two square banners with a lion on each banner. She discovered that this could be done in as few as four pieces. How did she manage it? Of course, to cut the British Lion would be an unpardonable offence, so you must be careful that no cut passes through any portion of either of them. Ladies are informed that no allowance whatever has to be made for "turnings," and no part of the material may be wasted. It is quite a simple little dissection puzzle if rightly attacked. Remember that the banners have to be perfect squares, though they need not be both of the same size.

Sources:

A Lady had a square piece of bunting with two lions on it, of which the illustration is an exactly reproduced reduction. She wished to cut the stuff into pieces that would fit together and form two square banners with a lion on each banner. She discovered that this could be done in as few as four pieces. How did she manage it? Of course, to cut the British Lion would be an unpardonable offence, so you must be careful that no cut passes through any portion of either of them. Ladies are informed that no allowance whatever has to be made for "turnings," and no part of the material may be wasted. It is quite a simple little dissection puzzle if rightly attacked. Remember that the banners have to be perfect squares, though they need not be both of the same size.

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 171

-

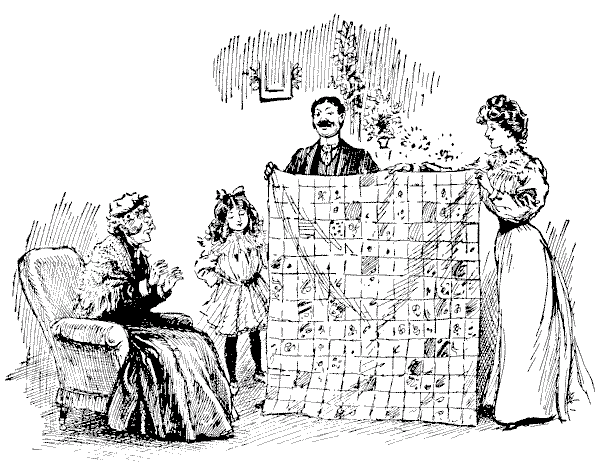

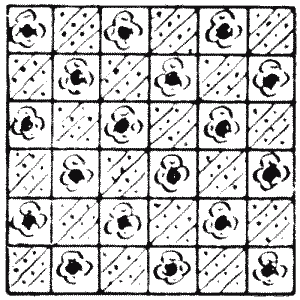

MRS. SMILEY'S CHRISTMAS PRESENT

Mrs. Smiley's expression of pleasure was sincere when her six granddaughters sent to her, as a Christmas present, a very pretty patchwork quilt, which they had made with their own hands. It was constructed of square pieces of silk material, all of one size, and as they made a large quilt with fourteen of these little squares on each side, it is obvious that just `196` pieces had been stitched into it. Now, the six granddaughters each contributed a part of the work in the form of a perfect square (all six portions being different in size), but in order to join them up to form the square quilt it was necessary that the work of one girl should be unpicked into three separate pieces. Can you show how the joins might have been made? Of course, no portion can be turned over. Sources:Topics:Geometry Number Theory Arithmetic Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems

Sources:Topics:Geometry Number Theory Arithmetic Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 172

-

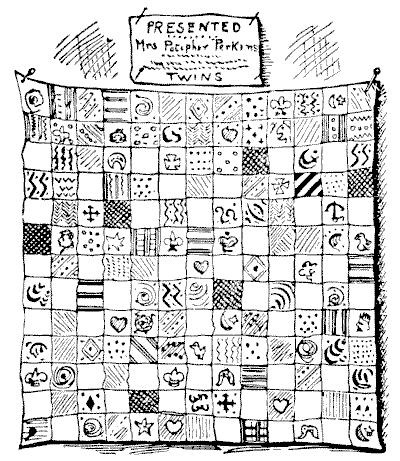

MRS. PERKINS'S QUILT

It will be seen that in this case the square patchwork quilt is built up of `169` pieces. The puzzle is to find the smallest possible number of square portions of which the quilt could be composed and show how they might be joined together. Or, to put it the reverse way, divide the quilt into as few square portions as possible by merely cutting the stitches.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Minimum and Maximum Problems / Optimization Problems Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems

It will be seen that in this case the square patchwork quilt is built up of `169` pieces. The puzzle is to find the smallest possible number of square portions of which the quilt could be composed and show how they might be joined together. Or, to put it the reverse way, divide the quilt into as few square portions as possible by merely cutting the stitches.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Minimum and Maximum Problems / Optimization Problems Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 173

-

THE SQUARES OF BROCADE

I happened to be paying a call at the house of a lady, when I took up from a table two lovely squares of brocade. They were beautiful specimens of Eastern workmanship—both of the same design, a delicate chequered pattern

."Are they not exquisite?" said my friend. "They were brought to me by a cousin who has just returned from India. Now, I want you to give me a little assistance. You see, I have decided to join them together so as to make one large square cushion-cover. How should I do this so as to mutilate the material as little as possible? Of course I propose to make my cuts only along the lines that divide the little chequers."

I cut the two squares in the manner desired into four pieces that would fit together and form another larger square, taking care that the pattern should match properly, and when I had finished I noticed that two of the pieces were of exactly the same area; that is, each of the two contained the same number of chequers. Can you show how the cuts were made in accordance with these conditions?

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 174

-

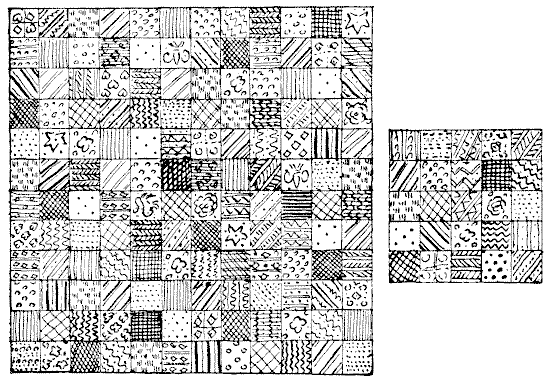

ANOTHER PATCHWORK PUZZLE

A lady was presented, by two of her girl friends, with the pretty pieces of silk patchwork shown in our illustration. It will be seen that both pieces are made up of squares all of the same size—one 12x12 and the other 5x5. She proposes to join them together and make one square patchwork quilt, 13x13, but, of course, she will not cut any of the material—merely cut the stitches where necessary and join together again. What perplexes her is this. A friend assures her that there need be no more than four pieces in all to join up for the new quilt. Could you show her how this little needlework puzzle is to be solved in so few pieces?

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems

A lady was presented, by two of her girl friends, with the pretty pieces of silk patchwork shown in our illustration. It will be seen that both pieces are made up of squares all of the same size—one 12x12 and the other 5x5. She proposes to join them together and make one square patchwork quilt, 13x13, but, of course, she will not cut any of the material—merely cut the stitches where necessary and join together again. What perplexes her is this. A friend assures her that there need be no more than four pieces in all to join up for the new quilt. Could you show her how this little needlework puzzle is to be solved in so few pieces?

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 175

-

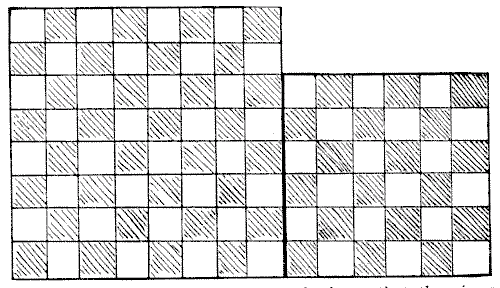

LINOLEUM CUTTING

The diagram herewith represents two separate pieces of linoleum. The chequered pattern is not repeated at the back, so that the pieces cannot be turned over. The puzzle is to cut the two squares into four pieces so that they shall fit together and form one perfect square `10`×`10`, so that the pattern shall properly match, and so that the larger piece shall have as small a portion as possible cut from it.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Area Calculation Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Pythagorean Theorem Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems

The diagram herewith represents two separate pieces of linoleum. The chequered pattern is not repeated at the back, so that the pieces cannot be turned over. The puzzle is to cut the two squares into four pieces so that they shall fit together and form one perfect square `10`×`10`, so that the pattern shall properly match, and so that the larger piece shall have as small a portion as possible cut from it.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Area Calculation Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Pythagorean Theorem Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 176

-

ANOTHER LINOLEUM PUZZLE

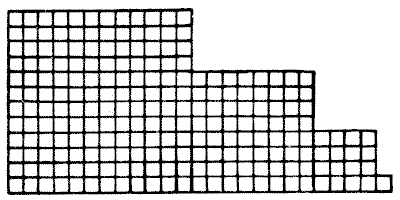

Can you cut this piece of linoleum into four pieces that will fit together and form a perfect square? Of course the cuts may only be made along the lines.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 177