Geometry

Geometry is the branch of mathematics concerned with the properties and relations of points, lines, surfaces, solids, and higher dimensional analogues. Expected questions involve calculating lengths, angles, areas, and volumes of various shapes, understanding geometric theorems, and solving problems related to spatial reasoning.

Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space Trigonometry Spherical Geometry Plane Geometry Vectors-

A PACKING PUZZLE

As we all know by experience, considerable ingenuity is often required in packing articles into a box if space is not to be unduly wasted. A man once told me that he had a large number of iron balls, all exactly two inches in diameter, and he wished to pack as many of these as possible into a rectangular box `24` `9/10` inches long, `22` `4/5` inches wide, and `14` inches deep. Now, what is the greatest number of the balls that he could pack into that box?Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space Arithmetic Minimum and Maximum Problems / Optimization Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 370

-

THE CIGAR PUZZLE

I once propounded the following puzzle in a London club, and for a considerable period it absorbed the attention of the members. They could make nothing of it, and considered it quite impossible of solution. And yet, as I shall show, the answer is remarkably simple.

Two men are seated at a square-topped table. One places an ordinary cigar (flat at one end, pointed at the other) on the table, then the other does the same, and so on alternately, a condition being that no cigar shall touch another. Which player should succeed in placing the last cigar, assuming that they each will play in the best possible manner? The size of the table top and the size of the cigar are not given, but in order to exclude the ridiculous answer that the table might be so diminutive as only to take one cigar, we will say that the table must not be less than `2` feet square and the cigar not more than `4`½ inches long. With those restrictions you may take any dimensions you like. Of course we assume that all the cigars are exactly alike in every respect. Should the first player, or the second player, win?

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Game Theory Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Symmetry- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 398

-

A CHESSBOARD FALLACY

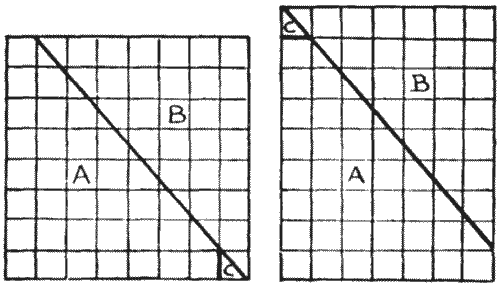

"Here is a diagram of a chessboard," he said. "You see there are sixty-four squares—eight by eight. Now I draw a straight line from the top left-hand corner, where the first and second squares meet, to the bottom right-hand corner. I cut along this line with the scissors, slide up the piece that I have marked B, and then clip off the little corner C by a cut along the first upright line. This little piece will exactly fit into its place at the top, and we now have an oblong with seven squares on one side and nine squares on the other. There are, therefore, now only sixty-three squares, because seven multiplied by nine makes sixty-three. Where on earth does that lost square go to? I have tried over and over again to catch the little beggar, but he always eludes me. For the life of me I cannot discover where he hides himself."

"It seems to be like the other old chessboard fallacy, and perhaps the explanation is the same," said Reginald—"that the pieces do not exactly fit."

"But they do fit," said Uncle John. "Try it, and you will see."

Later in the evening Reginald and George, were seen in a corner with their heads together, trying to catch that elusive little square, and it is only fair to record that before they retired for the night they succeeded in securing their prey, though some others of the company failed to see it when captured. Can the reader solve the little mystery?

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 413

-

THE FIVE PENNIES

Here is a really hard puzzle, and yet its conditions are so absurdly simple. Every reader knows how to place four pennies so that they are equidistant from each other. All you have to do is to arrange three of them flat on the table so that they touch one another in the form of a triangle, and lay the fourth penny on top in the centre. Then, as every penny touches every other penny, they are all at equal distances from one another. Now try to do the same thing with five pennies—place them so that every penny shall touch every other penny—and you will find it a different matter altogether.Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 419

-

THE DOVETAILED BLOCK

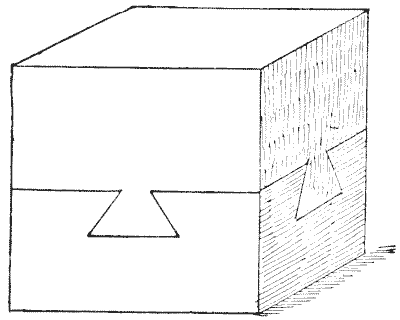

Here is a curious mechanical puzzle that was given to me some years ago, but I cannot say who first invented it. It consists of two solid blocks of wood securely dovetailed together. On the other two vertical sides that are not visible the appearance is precisely the same as on those shown. How were the pieces put together? When I published this little puzzle in a London newspaper I received (though they were unsolicited) quite a stack of models, in oak, in teak, in mahogany, rosewood, satinwood, elm, and deal; some half a foot in length, and others varying in size right down to a delicate little model about half an inch square. It seemed to create considerable interest.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space

Here is a curious mechanical puzzle that was given to me some years ago, but I cannot say who first invented it. It consists of two solid blocks of wood securely dovetailed together. On the other two vertical sides that are not visible the appearance is precisely the same as on those shown. How were the pieces put together? When I published this little puzzle in a London newspaper I received (though they were unsolicited) quite a stack of models, in oak, in teak, in mahogany, rosewood, satinwood, elm, and deal; some half a foot in length, and others varying in size right down to a delicate little model about half an inch square. It seemed to create considerable interest.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 424

-

PLACING HALFPENNIES

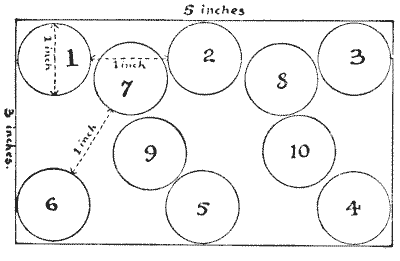

Here is an interesting little puzzle suggested to me by Mr. W. T. Whyte. Mark off on a sheet of paper a rectangular space `5` inches by `3` inches, and then find the greatest number of halfpennies that can be placed within the enclosure under the following conditions. A halfpenny is exactly an inch in diameter. Place your first halfpenny where you like, then place your second coin at exactly the distance of an inch from the first, the third an inch distance from the second, and so on. No halfpenny may touch another halfpenny or cross the boundary. Our illustration will make the matter perfectly clear. No. `2` coin is an inch from No. `1`; No. `3` an inch from No. `2`; No. `4` an inch from No. `3`; but after No. `10` is placed we can go no further in this attempt. Yet several more halfpennies might have been got in. How many can the reader place?

Sources:

Here is an interesting little puzzle suggested to me by Mr. W. T. Whyte. Mark off on a sheet of paper a rectangular space `5` inches by `3` inches, and then find the greatest number of halfpennies that can be placed within the enclosure under the following conditions. A halfpenny is exactly an inch in diameter. Place your first halfpenny where you like, then place your second coin at exactly the distance of an inch from the first, the third an inch distance from the second, and so on. No halfpenny may touch another halfpenny or cross the boundary. Our illustration will make the matter perfectly clear. No. `2` coin is an inch from No. `1`; No. `3` an inch from No. `2`; No. `4` an inch from No. `3`; but after No. `10` is placed we can go no further in this attempt. Yet several more halfpennies might have been got in. How many can the reader place?

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 429