Geometry

Geometry is the branch of mathematics concerned with the properties and relations of points, lines, surfaces, solids, and higher dimensional analogues. Expected questions involve calculating lengths, angles, areas, and volumes of various shapes, understanding geometric theorems, and solving problems related to spatial reasoning.

Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space Trigonometry Spherical Geometry Plane Geometry Vectors-

A QUESTION OF DEFINITION

"My property is exactly a mile square," said one landowner to another.

"Curiously enough, mine is a square mile," was the reply.

"Then there is no difference?"

Is this last statement correct?

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 124

-

THE CROSS AND THE TRIANGLE

Cut a Greek cross into six pieces that will form an equilateral triangle. This is another hard problem, and I will state here that a solution is practically impossible without a previous knowledge of my method of transforming an equilateral triangle into a square (see No. `26`, "Canterbury Puzzles").Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Area Calculation Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Triangles Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 144

-

THE BUN PUZZLE

The three circles represent three buns, and it is simply required to show how these may be equally divided among four boys. The buns must be regarded as of equal thickness throughout and of equal thickness to each other. Of course, they must be cut into as few pieces as possible. To simplify it I will state the rather surprising fact that only five pieces are necessary, from which it will be seen that one boy gets his share in two pieces and the other three receive theirs in a single piece. I am aware that this statement "gives away" the puzzle, but it should not destroy its interest to those who like to discover the "reason why."

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Area Calculation Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Circles Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Pythagorean Theorem Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems

The three circles represent three buns, and it is simply required to show how these may be equally divided among four boys. The buns must be regarded as of equal thickness throughout and of equal thickness to each other. Of course, they must be cut into as few pieces as possible. To simplify it I will state the rather surprising fact that only five pieces are necessary, from which it will be seen that one boy gets his share in two pieces and the other three receive theirs in a single piece. I am aware that this statement "gives away" the puzzle, but it should not destroy its interest to those who like to discover the "reason why."

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Area Calculation Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Circles Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Pythagorean Theorem Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 148

-

ANOTHER JOINER'S PROBLEM

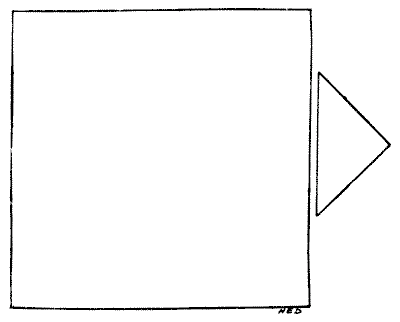

A joiner had two pieces of wood of the shapes and relative proportions shown in the diagram. He wished to cut them into as few pieces as possible so that they could be fitted together, without waste, to form a perfectly square table-top. How should he have done it? There is no necessity to give measurements, for if the smaller piece (which is half a square) be made a little too large or a little too small it will not affect the method of solution.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Area Calculation Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Pythagorean Theorem Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems

A joiner had two pieces of wood of the shapes and relative proportions shown in the diagram. He wished to cut them into as few pieces as possible so that they could be fitted together, without waste, to form a perfectly square table-top. How should he have done it? There is no necessity to give measurements, for if the smaller piece (which is half a square) be made a little too large or a little too small it will not affect the method of solution.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Area Calculation Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Pythagorean Theorem Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 152

-

A CUTTING-OUT PUZZLE

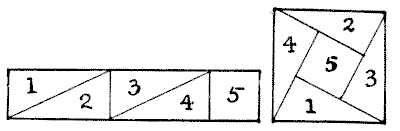

Here is a little cutting-out poser. I take a strip of paper, measuring five inches by one inch, and, by cutting it into five pieces, the parts fit together and form a square, as shown in the illustration. Now, it is quite an interesting puzzle to discover how we can do this in only four pieces. Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 153

-

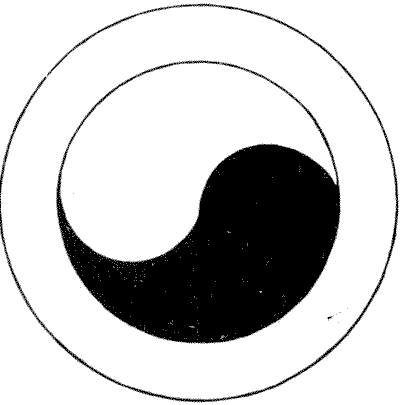

THE GREAT MONAD

Here is a symbol of tremendous antiquity which is worthy of notice. It is borne on the Korean ensign and merchant flag, and has been adopted as a trade sign by the Northern Pacific Railroad Company, though probably few are aware that it is the Great Monad, as shown in the sketch below. This sign is to the Chinaman what the cross is to the Christian. It is the sign of Deity and eternity, while the two parts into which the circle is divided are called the Yin and the Yan—the male and female forces of nature. A writer on the subject more than three thousand years ago is reported to have said in reference to it: "The illimitable produces the great extreme. The great extreme produces the two principles. The two principles produce the four quarters, and from the four quarters we develop the quadrature of the eight diagrams of Feuh-hi." I hope readers will not ask me to explain this, for I have not the slightest idea what it means. Yet I am persuaded that for ages the symbol has had occult and probably mathematical meanings for the esoteric student.

I will introduce the Monad in its elementary form. Here are three easy questions respecting this great symbol:—

(I.) Which has the greater area, the inner circle containing the Yin and the Yan, or the outer ring?

(II.) Divide the Yin and the Yan into four pieces of the same size and shape by one cut.

(III.) Divide the Yin and the Yan into four pieces of the same size, but different shape, by one straight cut.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Area Calculation Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Circles Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 158

-

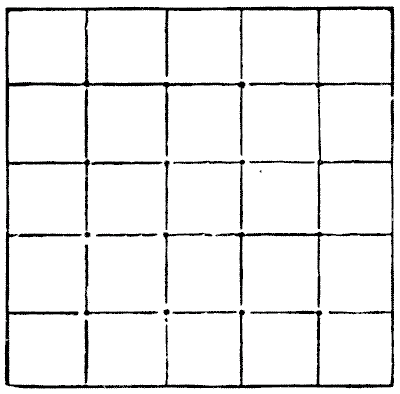

THE SQUARE OF VENEER

The following represents a piece of wood in my possession, `5` in. square. By markings on the surface it is divided into twenty-five square inches. I want to discover a way of cutting this piece of wood into the fewest possible pieces that will fit together and form two perfect squares of different sizes and of known dimensions. But, unfortunately, at every one of the sixteen intersections of the cross lines a small nail has been driven in at some time or other, and my fret-saw will be injured if it comes in contact with any of these. I have therefore to find a method of doing the work that will not necessitate my cutting through any of those sixteen points. How is it to be done? Remember, the exact dimensions of the two squares must be given. Sources:

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 159

-

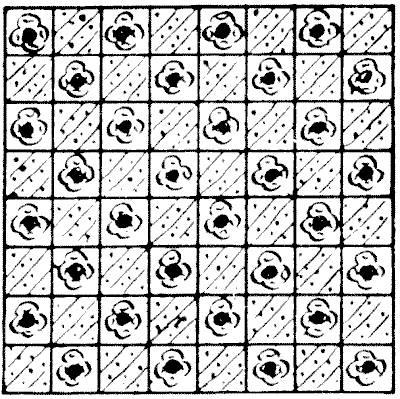

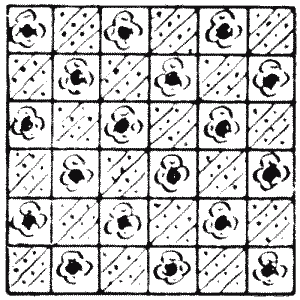

THE SQUARES OF BROCADE

I happened to be paying a call at the house of a lady, when I took up from a table two lovely squares of brocade. They were beautiful specimens of Eastern workmanship—both of the same design, a delicate chequered pattern

."Are they not exquisite?" said my friend. "They were brought to me by a cousin who has just returned from India. Now, I want you to give me a little assistance. You see, I have decided to join them together so as to make one large square cushion-cover. How should I do this so as to mutilate the material as little as possible? Of course I propose to make my cuts only along the lines that divide the little chequers."

I cut the two squares in the manner desired into four pieces that would fit together and form another larger square, taking care that the pattern should match properly, and when I had finished I noticed that two of the pieces were of exactly the same area; that is, each of the two contained the same number of chequers. Can you show how the cuts were made in accordance with these conditions?

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 174

-

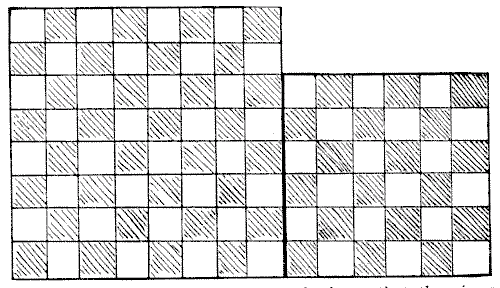

LINOLEUM CUTTING

The diagram herewith represents two separate pieces of linoleum. The chequered pattern is not repeated at the back, so that the pieces cannot be turned over. The puzzle is to cut the two squares into four pieces so that they shall fit together and form one perfect square `10`×`10`, so that the pattern shall properly match, and so that the larger piece shall have as small a portion as possible cut from it.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Area Calculation Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Pythagorean Theorem Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems

The diagram herewith represents two separate pieces of linoleum. The chequered pattern is not repeated at the back, so that the pieces cannot be turned over. The puzzle is to cut the two squares into four pieces so that they shall fit together and form one perfect square `10`×`10`, so that the pattern shall properly match, and so that the larger piece shall have as small a portion as possible cut from it.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Area Calculation Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Pythagorean Theorem Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 176

-

THE THREE RAILWAY STATIONS

As I sat in a railway carriage I noticed at the other end of the compartment a worthy squire, whom I knew by sight, engaged in conversation with another passenger, who was evidently a friend of his.

"How far have you to drive to your place from the railway station?" asked the stranger.

"Well," replied the squire, "if I get out at Appleford, it is just the same distance as if I go to Bridgefield, another fifteen miles farther on; and if I changed at Appleford and went thirteen miles from there to Carterton, it would still be the same distance. You see, I am equidistant from the three stations, so I get a good choice of trains."

Now I happened to know that Bridgefield is just fourteen miles from Carterton, so I amused myself in working out the exact distance that the squire had to drive home whichever station he got out at. What was the distance?

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Area Calculation Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Triangles Algebra -> Word Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 181