Geometry

Geometry is the branch of mathematics concerned with the properties and relations of points, lines, surfaces, solids, and higher dimensional analogues. Expected questions involve calculating lengths, angles, areas, and volumes of various shapes, understanding geometric theorems, and solving problems related to spatial reasoning.

Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space Trigonometry Spherical Geometry Plane Geometry Vectors-

THE BALL PROBLEM

A stonemason was engaged the other day in cutting out a round ball for the purpose of some architectural decoration, when a smart schoolboy came upon the scene.

"Look here," said the mason, "you seem to be a sharp youngster, can you tell me this? If I placed this ball on the level ground, how many other balls of the same size could I lay around it (also on the ground) so that every ball should touch this one?"

The boy at once gave the correct answer, and then put this little question to the mason:—

"If the surface of that ball contained just as many square feet as its volume contained cubic feet, what would be the length of its diameter?"

The stonemason could not give an answer. Could you have replied correctly to the mason's and the boy's questions?

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 188

-

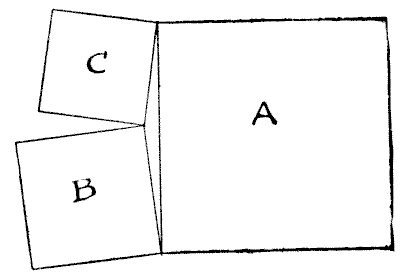

THE YORKSHIRE ESTATES

I was on a visit to one of the large towns of Yorkshire. While walking to the railway station on the day of my departure a man thrust a hand-bill upon me, and I took this into the railway carriage and read it at my leisure. It informed me that three Yorkshire neighbouring estates were to be offered for sale. Each estate was square in shape, and they joined one another at their corners, just as shown in the diagram. Estate A contains exactly `370` acres, B contains `116` acres, and C `74` acres.

Now, the little triangular bit of land enclosed by the three square estates was not offered for sale, and, for no reason in particular, I became curious as to the area of that piece. How many acres did it contain?

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Area Calculation Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Triangles Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Pythagorean Theorem- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 189

-

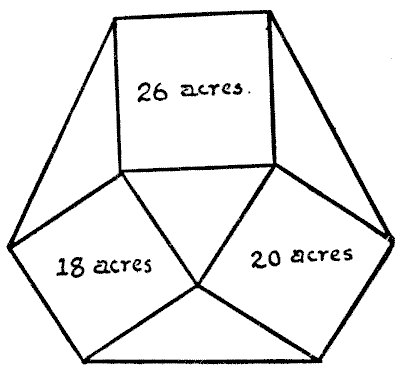

FARMER WURZEL'S ESTATE

I will now present another land problem. The demonstration of the answer that I shall give will, I think, be found both interesting and easy of comprehension.

Farmer Wurzel owned the three square fields shown in the annexed plan, containing respectively `18, 20`, and `26` acres. In order to get a ring-fence round his property he bought the four intervening triangular fields. The puzzle is to discover what was then the whole area of his estate.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Area Calculation Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Triangles Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Pythagorean Theorem- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 190

-

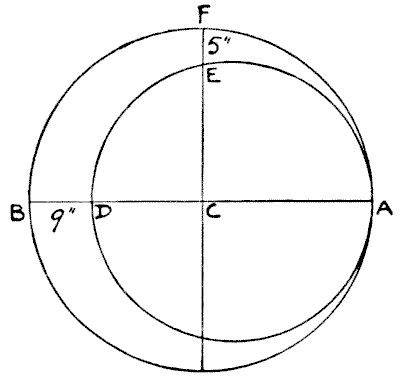

THE CRESCENT PUZZLE

Here is an easy geometrical puzzle. The crescent is formed by two circles, and C is the centre of the larger circle. The width of the crescent between B and D is `9` inches, and between E and F `5` inches. What are the diameters of the two circles?

Sources:

Here is an easy geometrical puzzle. The crescent is formed by two circles, and C is the centre of the larger circle. The width of the crescent between B and D is `9` inches, and between E and F `5` inches. What are the diameters of the two circles?

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 191

-

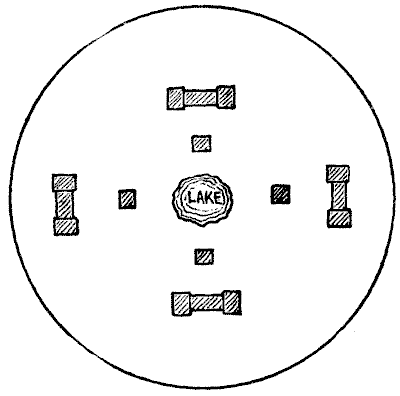

THE PUZZLE WALL

There was a small lake, around which four poor men built their cottages. Four rich men afterwards built their mansions, as shown in the illustration, and they wished to have the lake to themselves, so they instructed a builder to put up the shortest possible wall that would exclude the cottagers, but give themselves free access to the lake. How was the wall to be built?

Sources:

There was a small lake, around which four poor men built their cottages. Four rich men afterwards built their mansions, as shown in the illustration, and they wished to have the lake to themselves, so they instructed a builder to put up the shortest possible wall that would exclude the cottagers, but give themselves free access to the lake. How was the wall to be built?

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 192

-

THE SHEEP-FOLD

It is a curious fact that the answers always given to some of the best-known puzzles that appear in every little book of fireside recreations that has been published for the last fifty or a hundred years are either quite unsatisfactory or clearly wrong. Yet nobody ever seems to detect their faults. Here is an example:—A farmer had a pen made of fifty hurdles, capable of holding a hundred sheep only. Supposing he wanted to make it sufficiently large to hold double that number, how many additional hurdles must he have? Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 193

-

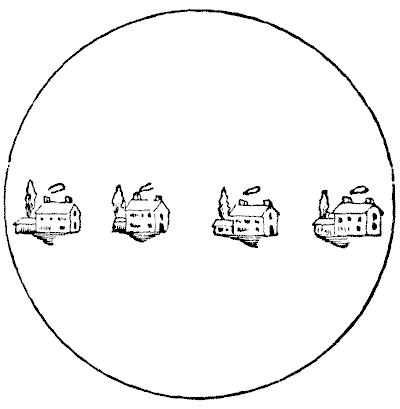

THE GARDEN WALLS

A speculative country builder has a circular field, on which he has erected four cottages, as shown in the illustration. The field is surrounded by a brick wall, and the owner undertook to put up three other brick walls, so that the neighbours should not be overlooked by each other, but the four tenants insist that there shall be no favouritism, and that each shall have exactly the same length of wall space for his wall fruit trees. The puzzle is to show how the three walls may be built so that each tenant shall have the same area of ground, and precisely the same length of wall.

Of course, each garden must be entirely enclosed by its walls, and it must be possible to prove that each garden has exactly the same length of wall. If the puzzle is properly solved no figures are necessary.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Area Calculation Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Circles Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 194

-

LADY BELINDA'S GARDEN

Lady Belinda is an enthusiastic gardener. In the illustration she is depicted in the act of worrying out a pleasant little problem which I will relate. One of her gardens is oblong in shape, enclosed by a high holly hedge, and she is turning it into a rosary for the cultivation of some of her choicest roses. She wants to devote exactly half of the area of the garden to the flowers, in one large bed, and the other half to be a path going all round it of equal breadth throughout. Such a garden is shown in the diagram at the foot of the picture. How is she to mark out the garden under these simple conditions? She has only a tape, the length of the garden, to do it with, and, as the holly hedge is so thick and dense, she must make all her measurements inside. Lady Belinda did not know the exact dimensions of the garden, and, as it was not necessary for her to know, I also give no dimensions. It is quite a simple task no matter what the size or proportions of the garden may be. Yet how many lady gardeners would know just how to proceed? The tape may be quite plain—that is, it need not be a graduated measure. Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Geometry -> Area Calculation Algebra -> Algebraic Techniques Algebra -> Equations

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Geometry -> Area Calculation Algebra -> Algebraic Techniques Algebra -> Equations- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 195

-

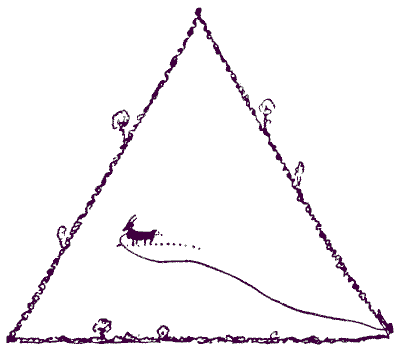

THE TETHERED GOAT

Here is a little problem that everybody should know how to solve. The goat is placed in a half-acre meadow, that is in shape an equilateral triangle. It is tethered to a post at one corner of the field. What should be the length of the tether (to the nearest inch) in order that the goat shall be able to eat just half the grass in the field? It is assumed that the goat can feed to the end of the tether.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Area Calculation Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Triangles Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Angle Calculation

Here is a little problem that everybody should know how to solve. The goat is placed in a half-acre meadow, that is in shape an equilateral triangle. It is tethered to a post at one corner of the field. What should be the length of the tether (to the nearest inch) in order that the goat shall be able to eat just half the grass in the field? It is assumed that the goat can feed to the end of the tether.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Area Calculation Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Triangles Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Angle Calculation- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 196

-

THE COMPASSES PUZZLE

It is curious how an added condition or restriction will sometimes convert an absurdly easy puzzle into an interesting and perhaps difficult one. I remember buying in the street many years ago a little mechanical puzzle that had a tremendous sale at the time. It consisted of a medal with holes in it, and the puzzle was to work a ring with a gap in it from hole to hole until it was finally detached. As I was walking along the street I very soon acquired the trick of taking off the ring with one hand while holding the puzzle in my pocket. A friend to whom I showed the little feat set about accomplishing it himself, and when I met him some days afterwards he exhibited his proficiency in the art. But he was a little taken aback when I then took the puzzle from him and, while simply holding the medal between the finger and thumb of one hand, by a series of little shakes and jerks caused the ring, without my even touching it, to fall off upon the floor. The following little poser will probably prove a rather tough nut for a great many readers, simply on account of the restricted conditions:—

Show how to find exactly the middle of any straight line by means of the compasses only. You are not allowed to use any ruler, pencil, or other article—only the compasses; and no trick or dodge, such as folding the paper, will be permitted. You must simply use the compasses in the ordinary legitimate way.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Circles- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 197