Geometry

Geometry is the branch of mathematics concerned with the properties and relations of points, lines, surfaces, solids, and higher dimensional analogues. Expected questions involve calculating lengths, angles, areas, and volumes of various shapes, understanding geometric theorems, and solving problems related to spatial reasoning.

Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space Trigonometry Spherical Geometry Plane Geometry Vectors-

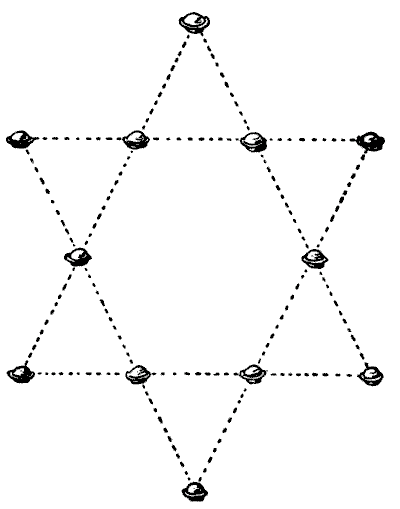

THE TWELVE MINCE-PIES

It will be seen in our illustration how twelve mince-pies may be placed on the table so as to form six straight rows with four pies in every row. The puzzle is to remove only four of them to new positions so that there shall be seven straight rows with four in every row. Which four would you remove, and where would you replace them? Sources:

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 211

-

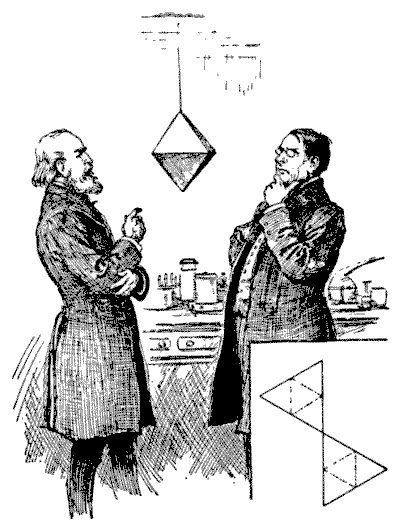

THE FLY ON THE OCTAHEDRON

"Look here," said the professor to his colleague, "I have been watching that fly on the octahedron, and it confines its walks entirely to the edges. What can be its reason for avoiding the sides?"

"Perhaps it is trying to solve some route problem," suggested the other. "Supposing it to start from the top point, how many different routes are there by which it may walk over all the edges, without ever going twice along the same edge in any route?"

The problem was a harder one than they expected, and after working at it during leisure moments for several days their results did not agree—in fact, they were both wrong. If the reader is surprised at their failure, let him attempt the little puzzle himself. I will just explain that the octahedron is one of the five regular, or Platonic, bodies, and is contained under eight equal and equilateral triangles. If you cut out the two pieces of cardboard of the shape shown in the margin of the illustration, cut half through along the dotted lines and then bend them and put them together, you will have a perfect octahedron. In any route over all the edges it will be found that the fly must end at the point of departure at the top.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space -> Polyhedra -> Regular Polyhedra- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 245

-

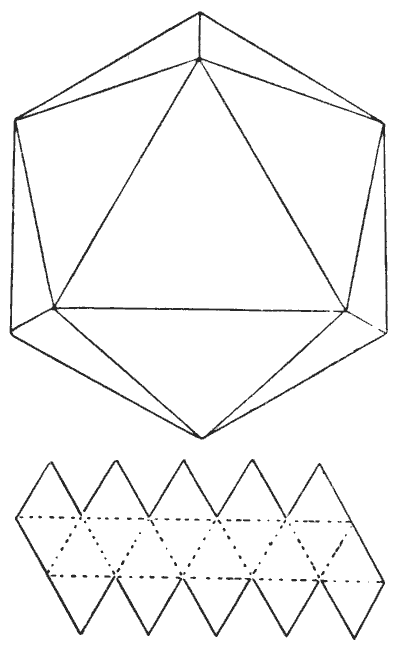

THE ICOSAHEDRON PUZZLE

The icosahedron is another of the five regular, or Platonic, bodies having all their sides, angles, and planes similar and equal. It is bounded by twenty similar equilateral triangles. If you cut out a piece of cardboard of the form shown in the smaller diagram, and cut half through along the dotted lines, it will fold up and form a perfect icosahedron.

Now, a Platonic body does not mean a heavenly body; but it will suit the purpose of our puzzle if we suppose there to be a habitable planet of this shape. We will also suppose that, owing to a superfluity of water, the only dry land is along the edges, and that the inhabitants have no knowledge of navigation. If every one of those edges is `10,000` miles long and a solitary traveller is placed at the North Pole (the highest point shown), how far will he have to travel before he will have visited every habitable part of the planet—that is, have traversed every one of the edges?

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space -> Polyhedra -> Regular Polyhedra

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space -> Polyhedra -> Regular Polyhedra- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 246

-

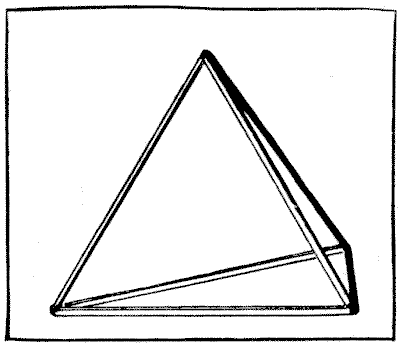

BUILDING THE TETRAHEDRON

I possess a tetrahedron, or triangular pyramid, formed of six sticks glued together, as shown in the illustration. Can you count correctly the number of different ways in which these six sticks might have been stuck together so as to form the pyramid?

Some friends worked at it together one evening, each person providing himself with six lucifer matches to aid his thoughts; but it was found that no two results were the same. You see, if we remove one of the sticks and turn it round the other way, that will be a different pyramid. If we make two of the sticks change places the result will again be different. But remember that every pyramid may be made to stand on either of its four sides without being a different one. How many ways are there altogether?

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space -> Polyhedra

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space -> Polyhedra- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 280

-

PAINTING A PYRAMID

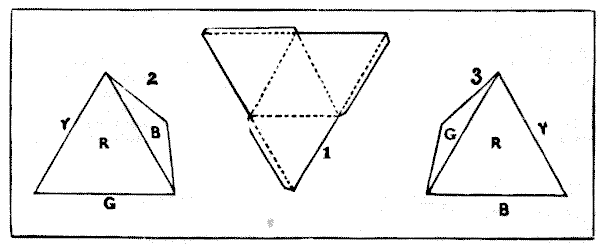

This puzzle concerns the painting of the four sides of a tetrahedron, or triangular pyramid. If you cut out a piece of cardboard of the triangular shape shown in Fig. `1`, and then cut half through along the dotted lines, it will fold up and form a perfect triangular pyramid. And I would first remind my readers that the primary colours of the solar spectrum are seven—violet, indigo, blue, green, yellow, orange, and red. When I was a child I was taught to remember these by the ungainly word formed by the initials of the colours, "Vibgyor." In how many different ways may the triangular pyramid be coloured, using in every case one, two, three, or four colours of the solar spectrum? Of course a side can only receive a single colour, and no side can be left uncoloured. But there is one point that I must make quite clear. The four sides are not to be regarded as individually distinct. That is to say, if you paint your pyramid as shown in Fig. `2` (where the bottom side is green and the other side that is out of view is yellow), and then paint another in the order shown in Fig. `3`, these are really both the same and count as one way. For if you tilt over No. `2` to the right it will so fall as to represent No. `3`. The avoidance of repetitions of this kind is the real puzzle of the thing. If a coloured pyramid cannot be placed so that it exactly resembles in its colours and their relative order another pyramid, then they are different. Remember that one way would be to colour all the four sides red, another to colour two sides green, and the remaining sides yellow and blue; and so on.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space -> Polyhedra

In how many different ways may the triangular pyramid be coloured, using in every case one, two, three, or four colours of the solar spectrum? Of course a side can only receive a single colour, and no side can be left uncoloured. But there is one point that I must make quite clear. The four sides are not to be regarded as individually distinct. That is to say, if you paint your pyramid as shown in Fig. `2` (where the bottom side is green and the other side that is out of view is yellow), and then paint another in the order shown in Fig. `3`, these are really both the same and count as one way. For if you tilt over No. `2` to the right it will so fall as to represent No. `3`. The avoidance of repetitions of this kind is the real puzzle of the thing. If a coloured pyramid cannot be placed so that it exactly resembles in its colours and their relative order another pyramid, then they are different. Remember that one way would be to colour all the four sides red, another to colour two sides green, and the remaining sides yellow and blue; and so on.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space -> Polyhedra- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 281

-

THE CROSS TARGET

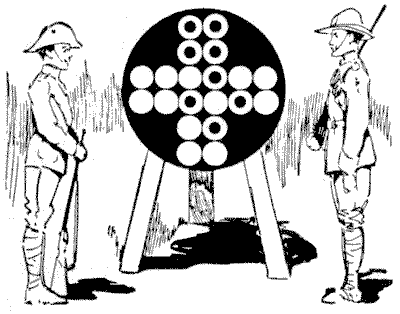

In the illustration we have a somewhat curious target designed by an eccentric sharpshooter. His idea was that in order to score you must hit four circles in as many shots so that those four shots shall form a square. It will be seen by the results recorded on the target that two attempts have been successful. The first man hit the four circles at the top of the cross, and thus formed his square. The second man intended to hit the four in the bottom arm, but his second shot, on the left, went too high. This compelled him to complete his four in a different way than he intended. It will thus be seen that though it is immaterial which circle you hit at the first shot, the second shot may commit you to a definite procedure if you are to get your square. Now, the puzzle is to say in just how many different ways it is possible to form a square on the target with four shots.

Sources:Topics:Geometry Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Grid Paper Geometry / Lattice Geometry

In the illustration we have a somewhat curious target designed by an eccentric sharpshooter. His idea was that in order to score you must hit four circles in as many shots so that those four shots shall form a square. It will be seen by the results recorded on the target that two attempts have been successful. The first man hit the four circles at the top of the cross, and thus formed his square. The second man intended to hit the four in the bottom arm, but his second shot, on the left, went too high. This compelled him to complete his four in a different way than he intended. It will thus be seen that though it is immaterial which circle you hit at the first shot, the second shot may commit you to a definite procedure if you are to get your square. Now, the puzzle is to say in just how many different ways it is possible to form a square on the target with four shots.

Sources:Topics:Geometry Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Grid Paper Geometry / Lattice Geometry- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 284

-

BOARDS WITH AN ODD NUMBER OF SQUARES

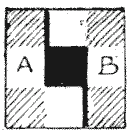

We will here consider the question of those boards that contain an odd number of squares. We will suppose that the central square is first cut out, so as to leave an even number of squares for division. Now, it is obvious that a square three by three can only be divided in one way, as shown in Fig. `1`. It will be seen that the pieces A and B are of the same size and shape, and that any other way of cutting would only produce the same shaped pieces, so remember that these variations are not counted as different ways. The puzzle I propose is to cut the board five by five (Fig. `2`) into two pieces of the same size and shape in as many different ways as possible. I have shown in the illustration one way of doing it. How many different ways are there altogether? A piece which when turned over resembles another piece is not considered to be of a different shape.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Symmetry Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Grid Paper Geometry / Lattice Geometry

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Symmetry Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Grid Paper Geometry / Lattice Geometry- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 290

-

THE YACHT RACE

Now then, ye land-lubbers, hoist your baby-jib-topsails, break out your spinnakers, ease off your balloon sheets, and get your head-sails set!

Our race consists in starting from the point at which the yacht is lying in the illustration and touching every one of the sixty-four buoys in fourteen straight courses, returning in the final tack to the buoy from which we start. The seventh course must finish at the buoy from which a flag is flying.

This puzzle will call for a lot of skilful seamanship on account of the sharp angles at which it will occasionally be necessary to tack. The point of a lead pencil and a good nautical eye are all the outfit that we require.

This is difficult, because of the condition as to the flag-buoy, and because it is a re-entrant tour. But again we are allowed those oblique lines.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Angle Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Grid Paper Geometry / Lattice Geometry- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 330

-

COUNTING THE RECTANGLES

Can you say correctly just how many squares and other rectangles the chessboard contains? In other words, in how great a number of different ways is it possible to indicate a square or other rectangle enclosed by lines that separate the squares of the board? Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 347

-

THE BARREL PUZZLE

The men in the illustration are disputing over the liquid contents of a barrel. What the particular liquid is it is impossible to say, for we are unable to look into the barrel; so we will call it water. One man says that the barrel is more than half full, while the other insists that it is not half full. What is their easiest way of settling the point? It is not necessary to use stick, string, or implement of any kind for measuring. I give this merely as one of the simplest possible examples of the value of ordinary sagacity in the solving of puzzles. What are apparently very difficult problems may frequently be solved in a similarly easy manner if we only use a little common sense. Sources:

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 364