Combinatorics, Combinatorial Geometry

Combinatorial Geometry explores the connections between combinatorics and geometry. It deals with problems about arrangements, configurations, and properties of discrete geometric objects (points, lines, polygons). Questions often involve counting, existence proofs, and geometric inequalities.

Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems Grid Paper Geometry / Lattice Geometry-

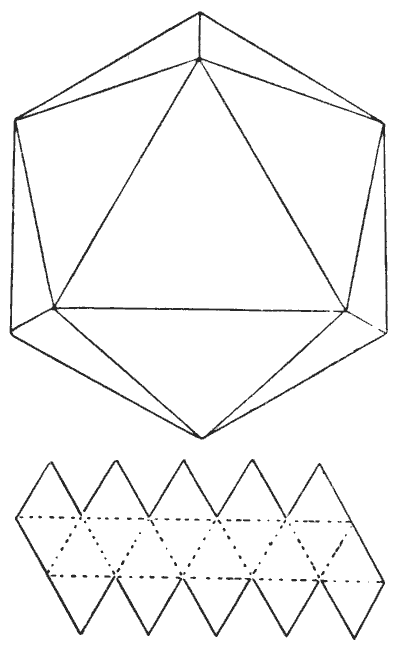

THE ICOSAHEDRON PUZZLE

The icosahedron is another of the five regular, or Platonic, bodies having all their sides, angles, and planes similar and equal. It is bounded by twenty similar equilateral triangles. If you cut out a piece of cardboard of the form shown in the smaller diagram, and cut half through along the dotted lines, it will fold up and form a perfect icosahedron.

Now, a Platonic body does not mean a heavenly body; but it will suit the purpose of our puzzle if we suppose there to be a habitable planet of this shape. We will also suppose that, owing to a superfluity of water, the only dry land is along the edges, and that the inhabitants have no knowledge of navigation. If every one of those edges is `10,000` miles long and a solitary traveller is placed at the North Pole (the highest point shown), how far will he have to travel before he will have visited every habitable part of the planet—that is, have traversed every one of the edges?

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space -> Polyhedra -> Regular Polyhedra

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space -> Polyhedra -> Regular Polyhedra- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 246

-

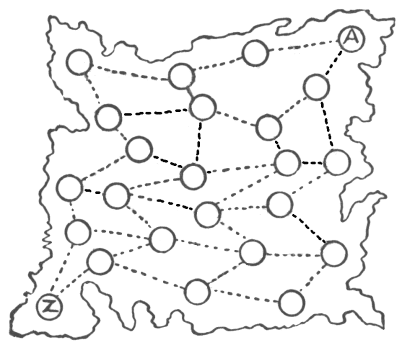

THE GRAND TOUR

One of the everyday puzzles of life is the working out of routes. If you are taking a holiday on your bicycle, or a motor tour, there always arises the question of how you are to make the best of your time and other resources. You have determined to get as far as some particular place, to include visits to such-and-such a town, to try to see something of special interest elsewhere, and perhaps to try to look up an old friend at a spot that will not take you much out of your way. Then you have to plan your route so as to avoid bad roads, uninteresting country, and, if possible, the necessity of a return by the same way that you went. With a map before you, the interesting puzzle is attacked and solved. I will present a little poser based on these lines.

I give a rough map of a country—it is not necessary to say what particular country—the circles representing towns and the dotted lines the railways connecting them. Now there lived in the town marked A a man who was born there, and during the whole of his life had never once left his native place. From his youth upwards he had been very industrious, sticking incessantly to his trade, and had no desire whatever to roam abroad. However, on attaining his fiftieth birthday he decided to see something of his country, and especially to pay a visit to a very old friend living at the town marked Z. What he proposed was this: that he would start from his home, enter every town once and only once, and finish his journey at Z. As he made up his mind to perform this grand tour by rail only, he found it rather a puzzle to work out his route, but he at length succeeded in doing so. How did he manage it? Do not forget that every town has to be visited once, and not more than once.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 250

-

BISHOPS—GUARDED

Now, how many bishops are necessary in order that every square shall be either occupied or attacked, and every bishop guarded by another bishop? And how may they be placed?Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Minimum and Maximum Problems / Optimization Problems Combinatorics -> Colorings -> Chessboard Coloring- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 298

-

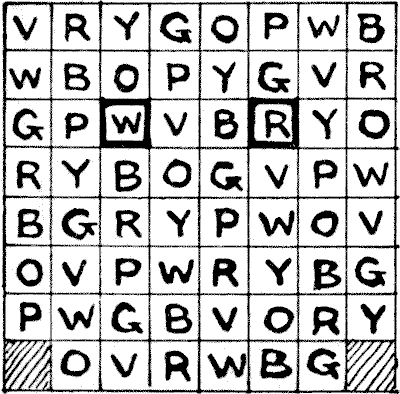

A PROBLEM IN MOSAICS

The art of producing pictures or designs by means of joining together pieces of hard substances, either naturally or artificially coloured, is of very great antiquity. It was certainly known in the time of the Pharaohs, and we find a reference in the Book of Esther to "a pavement of red, and blue, and white, and black marble." Some of this ancient work that has come down to us, especially some of the Roman mosaics, would seem to show clearly, even where design is not at first evident, that much thought was bestowed upon apparently disorderly arrangements. Where, for example, the work has been produced with a very limited number of colours, there are evidences of great ingenuity in preventing the same tints coming in close proximity. Lady readers who are familiar with the construction of patchwork quilts will know how desirable it is sometimes, when they are limited in the choice of material, to prevent pieces of the same stuff coming too near together. Now, this puzzle will apply equally to patchwork quilts or tesselated pavements.

It will be seen from the diagram how a square piece of flooring may be paved with sixty-two square tiles of the eight colours violet, red, yellow, green, orange, purple, white, and blue (indicated by the initial letters), so that no tile is in line with a similarly coloured tile, vertically, horizontally, or diagonally. Sixty-four such tiles could not possibly be placed under these conditions, but the two shaded squares happen to be occupied by iron ventilators.

The puzzle is this. These two ventilators have to be removed to the positions indicated by the darkly bordered tiles, and two tiles placed in those bottom corner squares. Can you readjust the thirty-two tiles so that no two of the same colour shall still be in line?

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 302

-

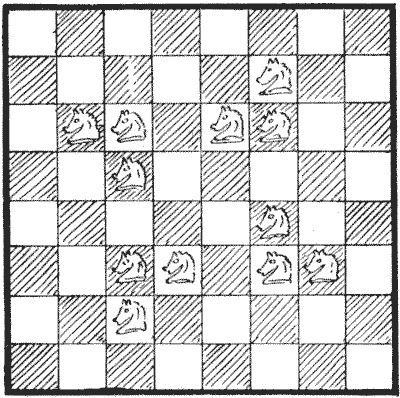

THE KNIGHT-GUARDS

The knight is the irresponsible low comedian of the chessboard. "He is a very uncertain, sneaking, and demoralizing rascal," says an American writer. "He can only move two squares, but makes up in the quality of his locomotion for its quantity, for he can spring one square sideways and one forward simultaneously, like a cat; can stand on one leg in the middle of the board and jump to any one of eight squares he chooses; can get on one side of a fence and blackguard three or four men on the other; has an objectionable way of inserting himself in safe places where he can scare the king and compel him to move, and then gobble a queen. For pure cussedness the knight has no equal, and when you chase him out of one hole he skips into another." Attempts have been made over and over again to obtain a short, simple, and exact definition of the move of the knight—without success. It really consists in moving one square like a rook, and then another square like a bishop—the two operations being done in one leap, so that it does not matter whether the first square passed over is occupied by another piece or not. It is, in fact, the only leaping move in chess. But difficult as it is to define, a child can learn it by inspection in a few minutes.

I have shown in the diagram how twelve knights (the fewest possible that will perform the feat) may be placed on the chessboard so that every square is either occupied or attacked by a knight. Examine every square in turn, and you will find that this is so. Now, the puzzle in this case is to discover what is the smallest possible number of knights that is required in order that every square shall be either occupied or attacked, and every knight protected by another knight. And how would you arrange them? It will be found that of the twelve shown in the diagram only four are thus protected by being a knight's move from another knight.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 319

-

THE LANGUISHING MAIDEN

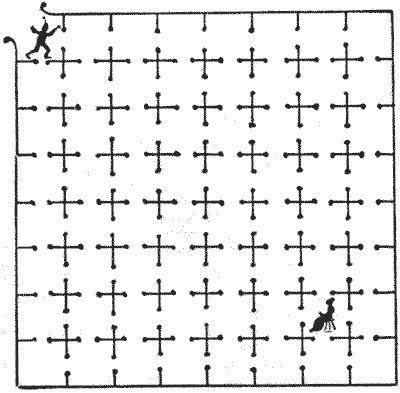

A wicked baron in the good old days imprisoned an innocent maiden in one of the deepest dungeons beneath the castle moat. It will be seen from our illustration that there were sixty-three cells in the dungeon, all connected by open doors, and the maiden was chained in the cell in which she is shown. Now, a valiant knight, who loved the damsel, succeeded in rescuing her from the enemy. Having gained an entrance to the dungeon at the point where he is seen, he succeeded in reaching the maiden after entering every cell once and only once. Take your pencil and try to trace out such a route. When you have succeeded, then try to discover a route in twenty-two straight paths through the cells. It can be done in this number without entering any cell a second time.

Sources:

A wicked baron in the good old days imprisoned an innocent maiden in one of the deepest dungeons beneath the castle moat. It will be seen from our illustration that there were sixty-three cells in the dungeon, all connected by open doors, and the maiden was chained in the cell in which she is shown. Now, a valiant knight, who loved the damsel, succeeded in rescuing her from the enemy. Having gained an entrance to the dungeon at the point where he is seen, he succeeded in reaching the maiden after entering every cell once and only once. Take your pencil and try to trace out such a route. When you have succeeded, then try to discover a route in twenty-two straight paths through the cells. It can be done in this number without entering any cell a second time.

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 322

-

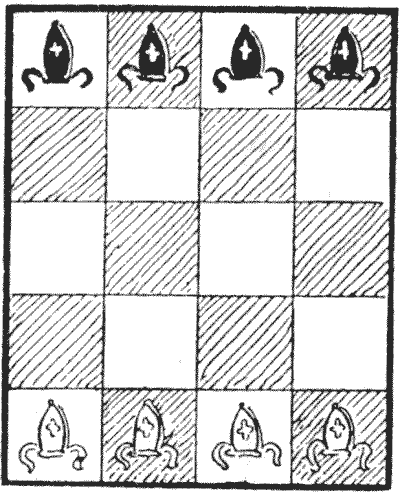

A NEW BISHOP'S PUZZLE

This is quite a fascinating little puzzle. Place eight bishops (four black and four white) on the reduced chessboard, as shown in the illustration. The problem is to make the black bishops change places with the white ones, no bishop ever attacking another of the opposite colour. They must move alternately—first a white, then a black, then a white, and so on. When you have succeeded in doing it at all, try to find the fewest possible moves.

If you leave out the bishops standing on black squares, and only play on the white squares, you will discover my last puzzle turned on its side.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Combinatorics -> Game Theory Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 327

-

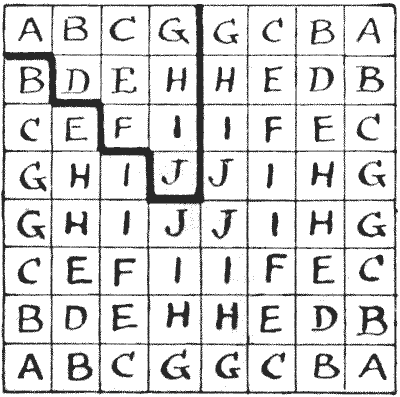

THE QUEEN'S TOUR

The puzzle of making a complete tour of the chessboard with the queen in the fewest possible moves (in which squares may be visited more than once) was first given by the late Sam Loyd in his Chess Strategy. But the solution shown below is the one he gave in American Chess-Nuts in `1868`. I have recorded at least six different solutions in the minimum number of moves—fourteen—but this one is the best of all, for reasons I will explain. If you will look at the lettered square you will understand that there are only ten really differently placed squares on a chessboard—those enclosed by a dark line—all the others are mere reversals or reflections. For example, every A is a corner square, and every J a central square. Consequently, as the solution shown has a turning-point at the enclosed D square, we can obtain a solution starting from and ending at any square marked D—by just turning the board about. Now, this scheme will give you a tour starting from any A, B, C, D, E, F, or H, while no other route that I know can be adapted to more than five different starting-points. There is no Queen's Tour in fourteen moves (remember a tour must be re-entrant) that may start from a G, I, or J. But we can have a non-re-entrant path over the whole board in fourteen moves, starting from any given square. Hence the following puzzle:—

If you will look at the lettered square you will understand that there are only ten really differently placed squares on a chessboard—those enclosed by a dark line—all the others are mere reversals or reflections. For example, every A is a corner square, and every J a central square. Consequently, as the solution shown has a turning-point at the enclosed D square, we can obtain a solution starting from and ending at any square marked D—by just turning the board about. Now, this scheme will give you a tour starting from any A, B, C, D, E, F, or H, while no other route that I know can be adapted to more than five different starting-points. There is no Queen's Tour in fourteen moves (remember a tour must be re-entrant) that may start from a G, I, or J. But we can have a non-re-entrant path over the whole board in fourteen moves, starting from any given square. Hence the following puzzle:—  Start from the J in the enclosed part of the lettered diagram and visit every square of the board in fourteen moves, ending wherever you like.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Game Theory Combinatorics -> Colorings -> Chessboard Coloring Puzzles and Rebuses

Start from the J in the enclosed part of the lettered diagram and visit every square of the board in fourteen moves, ending wherever you like.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Game Theory Combinatorics -> Colorings -> Chessboard Coloring Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 328

-

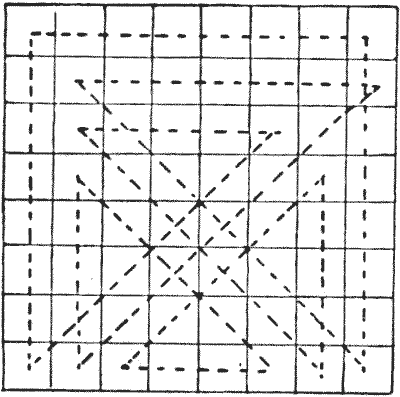

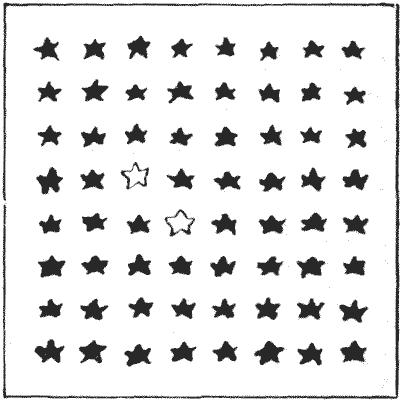

THE STAR PUZZLE

Put the point of your pencil on one of the white stars and (without ever lifting your pencil from the paper) strike out all the stars in fourteen continuous straight strokes, ending at the second white star. Your straight strokes may be in any direction you like, only every turning must be made on a star. There is no objection to striking out any star more than once.

In this case, where both your starting and ending squares are fixed inconveniently, you cannot obtain a solution by breaking a Queen's Tour, or in any other way by queen moves alone. But you are allowed to use oblique straight lines—such as from the upper white star direct to a corner star.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 329

-

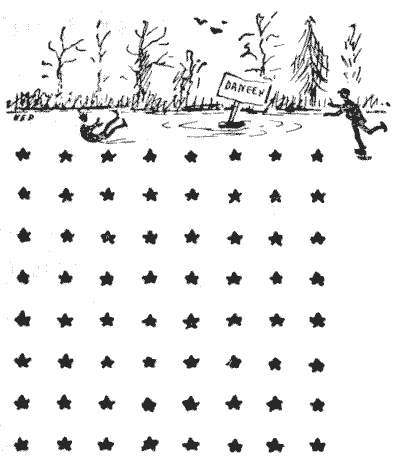

THE SCIENTIFIC SKATER

It will be seen that this skater has marked on the ice sixty-four points or stars, and he proposes to start from his present position near the corner and enter every one of the points in fourteen straight lines. How will he do it? Of course there is no objection to his passing over any point more than once, but his last straight stroke must bring him back to the position from which he started.

It is merely a matter of taking your pencil and starting from the spot on which the skater's foot is at present resting, and striking out all the stars in fourteen continuous straight lines, returning to the point from which you set out.

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 331