Geometry, Plane Geometry

Plane Geometry concerns figures and shapes on a flat, two-dimensional surface. It covers properties of points, lines, angles, polygons (like triangles and quadrilaterals), and circles. Questions typically involve proofs, constructions, and calculations related to these elements.

Area Calculation Triangles Circles Symmetry Angle Calculation Pythagorean Theorem Triangle Inequality-

5 Lines, 8 Intersections

Draw 5 lines such that there are exactly 8 points of intersection between them.

Sources: -

Blue or Orange?

In the diagram, there is a square ABCD and a parallelogram BCEF. Which area is larger: the blue or the orange?

Sources: -

The Orange Path

In the illustration, there is an orange path surrounding a blue square. The area of the path is 44% of the area of the square.

What is the width of the orange path as a percentage relative to the side length of the blue square?Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Geometry -> Area Calculation Algebra -> Word Problems Arithmetic -> Percentages -

Star of David in a Circle

Eight points are given on a circle. In how many different ways can a Star of David be drawn with vertices at these points?

Note: A Star of David is a figure obtained when two triangles intersect and their sides create exactly 6 intersection points.

Sources: -

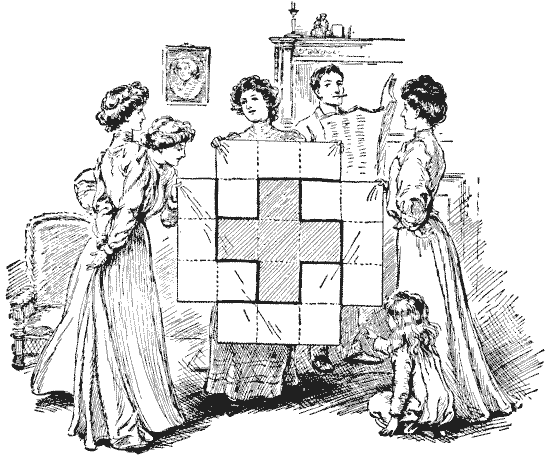

THE SILK PATCHWORK

The lady members of the Wilkinson family had made a simple patchwork quilt, as a small Christmas present, all composed of square pieces of the same size, as shown in the illustration. It only lacked the four corner pieces to make it complete. Somebody pointed out to them that if you unpicked the Greek cross in the middle and then cut the stitches along the dark joins, the four pieces all of the same size and shape would fit together and form a square. This the reader knows, from the solution in Fig. `39`, is quite easily done. But George Wilkinson suddenly suggested to them this poser. He said, "Instead of picking out the cross entire, and forming the square from four equal pieces, can you cut out a square entire and four equal pieces that will form a perfect Greek cross?" The puzzle is, of course, now quite easy. Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 142

-

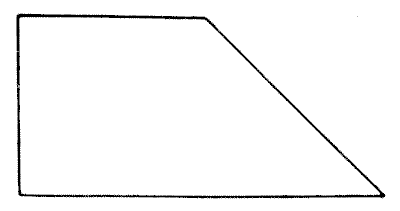

AN EASY DISSECTION PUZZLE

First, cut out a piece of paper or cardboard of the shape shown in the illustration. It will be seen at once that the proportions are simply those of a square attached to half of another similar square, divided diagonally. The puzzle is to cut it into four pieces all of precisely the same size and shape.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 146

-

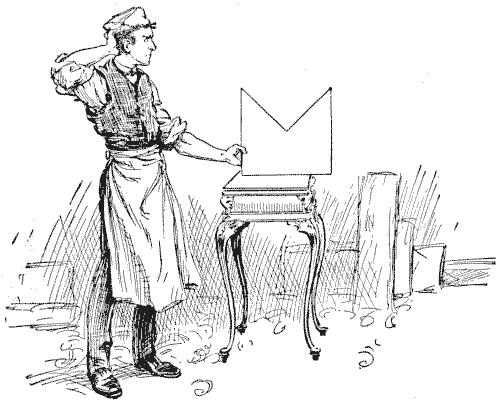

DISSECTING A MITRE

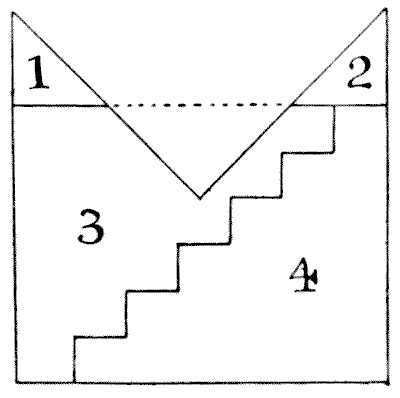

The figure that is perplexing the carpenter in the illustration represents a mitre. It will be seen that its proportions are those of a square with one quarter removed. The puzzle is to cut it into five pieces that will fit together and form a perfect square. I show an attempt, published in America, to perform the feat in four pieces, based on what is known as the "step principle," but it is a fallacy.

We are told first to cut oft the pieces `1` and `2` and pack them into the triangular space marked off by the dotted line, and so form a rectangle.

So far, so good. Now, we are directed to apply the old step principle, as shown, and, by moving down the piece `4` one step, form the required square. But, unfortunately, it does not produce a square: only an oblong. Call the three long sides of the mitre `84` in. each. Then, before cutting the steps, our rectangle in three pieces will be `84`×`63`. The steps must be `10`½ in. in height and `12` in. in breadth. Therefore, by moving down a step we reduce by `12` in. the side `84` in. and increase by `10`½ in. the side `63` in. Hence our final rectangle must be `72` in. × `73`½ in., which certainly is not a square! The fact is, the step principle can only be applied to rectangles with sides of particular relative lengths. For example, if the shorter side in this case were `61` `5/7` (instead of `63`), then the step method would apply. For the steps would then be `10` `2/7` in. in height and `12` in. in breadth. Note that `61` `5/7` × `84`= the square of `72`. At present no solution has been found in four pieces, and I do not believe one possible.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 150

-

THE JOINER'S PROBLEM

I have often had occasion to remark on the practical utility of puzzles, arising out of an application to the ordinary affairs of life of the little tricks and "wrinkles" that we learn while solving recreation problems. The joiner, in the illustration, wants to cut the piece of wood into as few pieces as possible to form a square table-top, without any waste of material. How should he go to work? How many pieces would you require?

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems

The joiner, in the illustration, wants to cut the piece of wood into as few pieces as possible to form a square table-top, without any waste of material. How should he go to work? How many pieces would you require?

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 151

-

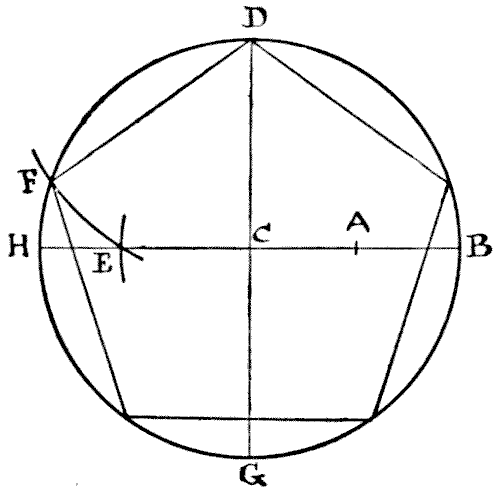

THE PENTAGON AND SQUARE

I wonder how many of my readers, amongst those who have not given any close attention to the elements of geometry, could draw a regular pentagon, or five-sided figure, if they suddenly required to do so. A regular hexagon, or six-sided figure, is easy enough, for everybody knows that all you have to do is to describe a circle and then, taking the radius as the length of one of the sides, mark off the six points round the circumference. But a pentagon is quite another matter. So, as my puzzle has to do with the cutting up of a regular pentagon, it will perhaps be well if I first show my less experienced readers how this figure is to be correctly drawn. Describe a circle and draw the two lines H B and D G, in the diagram, through the centre at right angles. Now find the point A, midway between C and B. Next place the point of your compasses at A and with the distance A D describe the arc cutting H B at E. Then place the point of your compasses at D and with the distance D E describe the arc cutting the circumference at F. Now, D F is one of the sides of your pentagon, and you have simply to mark off the other sides round the circle. Quite simple when you know how, but otherwise somewhat of a poser. Having formed your pentagon, the puzzle is to cut it into the fewest possible pieces that will fit together and form a perfect square.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space -> Polyhedra -> Regular Polyhedra

Having formed your pentagon, the puzzle is to cut it into the fewest possible pieces that will fit together and form a perfect square.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space -> Polyhedra -> Regular Polyhedra- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 155

-

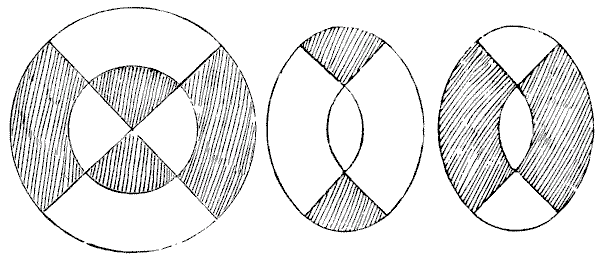

THE TABLE-TOP AND STOOLS

I have frequently had occasion to show that the published answers to a great many of the oldest and most widely known puzzles are either quite incorrect or capable of improvement. I propose to consider the old poser of the table-top and stools that most of my readers have probably seen in some form or another in books compiled for the recreation of childhood.

The story is told that an economical and ingenious schoolmaster once wished to convert a circular table-top, for which he had no use, into seats for two oval stools, each with a hand-hole in the centre. He instructed the carpenter to make the cuts as in the illustration and then join the eight pieces together in the manner shown. So impressed was he with the ingenuity of his performance that he set the puzzle to his geometry class as a little study in dissection. But the remainder of the story has never been published, because, so it is said, it was a characteristic of the principals of academies that they would never admit that they could err. I get my information from a descendant of the original boy who had most reason to be interested in the matter.

The clever youth suggested modestly to the master that the hand-holes were too big, and that a small boy might perhaps fall through them. He therefore proposed another way of making the cuts that would get over this objection. For his impertinence he received such severe chastisement that he became convinced that the larger the hand-hole in the stools the more comfortable might they be.

Now what was the method the boy proposed?

Can you show how the circular table-top may be cut into eight pieces that will fit together and form two oval seats for stools (each of exactly the same size and shape) and each having similar hand-holes of smaller dimensions than in the case shown above? Of course, all the wood must be used.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 157