Geometry, Plane Geometry

Plane Geometry concerns figures and shapes on a flat, two-dimensional surface. It covers properties of points, lines, angles, polygons (like triangles and quadrilaterals), and circles. Questions typically involve proofs, constructions, and calculations related to these elements.

Area Calculation Triangles Circles Symmetry Angle Calculation Pythagorean Theorem Triangle Inequality-

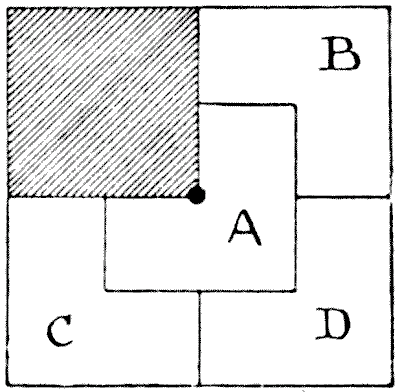

THE FOUR SONS

Readers will recognize the diagram as a familiar friend of their youth. A man possessed a square-shaped estate. He bequeathed to his widow the quarter of it that is shaded off. The remainder was to be divided equitably amongst his four sons, so that each should receive land of exactly the same area and exactly similar in shape. We are shown how this was done. But the remainder of the story is not so generally known. In the centre of the estate was a well, indicated by the dark spot, and Benjamin, Charles, and David complained that the division was not "equitable," since Alfred had access to this well, while they could not reach it without trespassing on somebody else's land. The puzzle is to show how the estate is to be apportioned so that each son shall have land of the same shape and area, and each have access to the well without going off his own land. Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 180

-

THE CLOTHES LINE PUZZLE

A boy tied a clothes line from the top of each of two poles to the base of the other. He then proposed to his father the following question. As one pole was exactly seven feet above the ground and the other exactly five feet, what was the height from the ground where the two cords crossed one another? Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 186

-

LADY BELINDA'S GARDEN

Lady Belinda is an enthusiastic gardener. In the illustration she is depicted in the act of worrying out a pleasant little problem which I will relate. One of her gardens is oblong in shape, enclosed by a high holly hedge, and she is turning it into a rosary for the cultivation of some of her choicest roses. She wants to devote exactly half of the area of the garden to the flowers, in one large bed, and the other half to be a path going all round it of equal breadth throughout. Such a garden is shown in the diagram at the foot of the picture. How is she to mark out the garden under these simple conditions? She has only a tape, the length of the garden, to do it with, and, as the holly hedge is so thick and dense, she must make all her measurements inside. Lady Belinda did not know the exact dimensions of the garden, and, as it was not necessary for her to know, I also give no dimensions. It is quite a simple task no matter what the size or proportions of the garden may be. Yet how many lady gardeners would know just how to proceed? The tape may be quite plain—that is, it need not be a graduated measure. Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Geometry -> Area Calculation Algebra -> Algebraic Techniques Algebra -> Equations

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Geometry -> Area Calculation Algebra -> Algebraic Techniques Algebra -> Equations- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 195

-

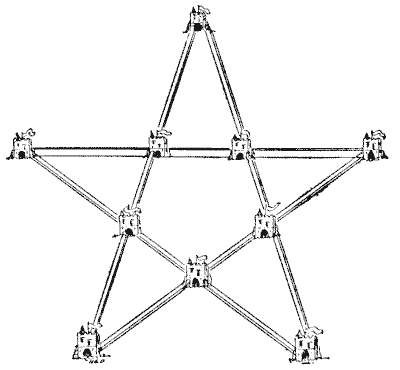

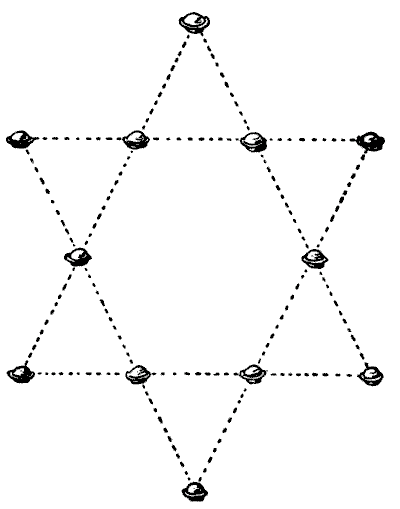

THE KING AND THE CASTLES

There was once, in ancient times, a powerful king, who had eccentric ideas on the subject of military architecture. He held that there was great strength and economy in symmetrical forms, and always cited the example of the bees, who construct their combs in perfect hexagonal cells, to prove that he had nature to support him. He resolved to build ten new castles in his country all to be connected by fortified walls, which should form five lines with four castles in every line. The royal architect presented his preliminary plan in the form I have shown. But the monarch pointed out that every castle could be approached from the outside, and commanded that the plan should be so modified that as many castles as possible should be free from attack from the outside, and could only be reached by crossing the fortified walls. The architect replied that he thought it impossible so to arrange them that even one castle, which the king proposed to use as a royal residence, could be so protected, but his majesty soon enlightened him by pointing out how it might be done. How would you have built the ten castles and fortifications so as best to fulfil the king's requirements? Remember that they must form five straight lines with four castles in every line. Sources:

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 206

-

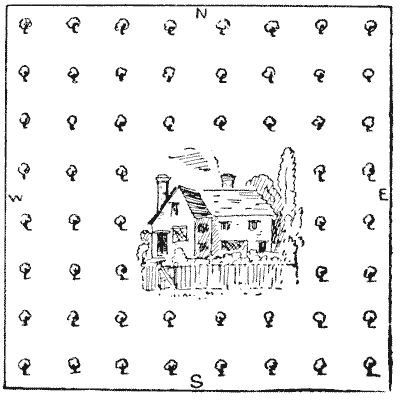

CHERRIES AND PLUMS

The illustration is a plan of a cottage as it stands surrounded by an orchard of fifty-five trees. Ten of these trees are cherries, ten are plums, and the remainder apples. The cherries are so planted as to form five straight lines, with four cherry trees in every line. The plum trees are also planted so as to form five straight lines with four plum trees in every line. The puzzle is to show which are the ten cherry trees and which are the ten plums. In order that the cherries and plums should have the most favourable aspect, as few as possible (under the conditions) are planted on the north and east sides of the orchard. Of course in picking out a group of ten trees (cherry or plum, as the case may be) you ignore all intervening trees. That is to say, four trees may be in a straight line irrespective of other trees (or the house) being in between. After the last puzzle this will be quite easy.

Sources:

The illustration is a plan of a cottage as it stands surrounded by an orchard of fifty-five trees. Ten of these trees are cherries, ten are plums, and the remainder apples. The cherries are so planted as to form five straight lines, with four cherry trees in every line. The plum trees are also planted so as to form five straight lines with four plum trees in every line. The puzzle is to show which are the ten cherry trees and which are the ten plums. In order that the cherries and plums should have the most favourable aspect, as few as possible (under the conditions) are planted on the north and east sides of the orchard. Of course in picking out a group of ten trees (cherry or plum, as the case may be) you ignore all intervening trees. That is to say, four trees may be in a straight line irrespective of other trees (or the house) being in between. After the last puzzle this will be quite easy.

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 207

-

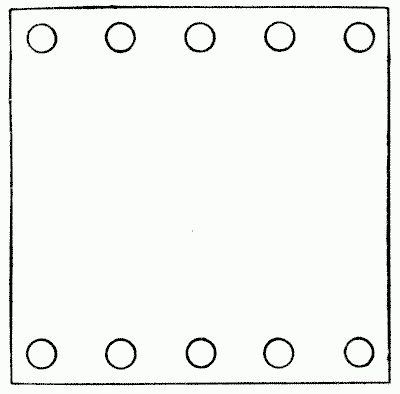

THE TEN COINS

Place ten pennies on a large sheet of paper or cardboard, as shown in the diagram, five on each edge. Now remove four of the coins, without disturbing the others, and replace them on the paper so that the ten shall form five straight lines with four coins in every line. This in itself is not difficult, but you should try to discover in how many different ways the puzzle may be solved, assuming that in every case the two rows at starting are exactly the same. Sources:

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 210

-

THE TWELVE MINCE-PIES

It will be seen in our illustration how twelve mince-pies may be placed on the table so as to form six straight rows with four pies in every row. The puzzle is to remove only four of them to new positions so that there shall be seven straight rows with four in every row. Which four would you remove, and where would you replace them? Sources:

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 211

-

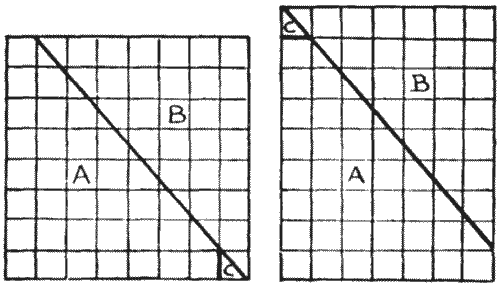

A CHESSBOARD FALLACY

"Here is a diagram of a chessboard," he said. "You see there are sixty-four squares—eight by eight. Now I draw a straight line from the top left-hand corner, where the first and second squares meet, to the bottom right-hand corner. I cut along this line with the scissors, slide up the piece that I have marked B, and then clip off the little corner C by a cut along the first upright line. This little piece will exactly fit into its place at the top, and we now have an oblong with seven squares on one side and nine squares on the other. There are, therefore, now only sixty-three squares, because seven multiplied by nine makes sixty-three. Where on earth does that lost square go to? I have tried over and over again to catch the little beggar, but he always eludes me. For the life of me I cannot discover where he hides himself."

"It seems to be like the other old chessboard fallacy, and perhaps the explanation is the same," said Reginald—"that the pieces do not exactly fit."

"But they do fit," said Uncle John. "Try it, and you will see."

Later in the evening Reginald and George, were seen in a corner with their heads together, trying to catch that elusive little square, and it is only fair to record that before they retired for the night they succeeded in securing their prey, though some others of the company failed to see it when captured. Can the reader solve the little mystery?

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 413

-

Question

There is a billiard table in the shape of a triangle whose angles are equal to \(90^{\circ}\), \(30^{\circ}\) and \(60^{\circ}\).

Given a right triangle shaped billiard table, with "pockets" in its corners. One of its acute angles is \(30^{\circ}\). From this corner (the thirty-degree angle) a ball is launched towards the midpoint of the opposite side of the triangle (the median). Prove that if the ball is reflected more than eight times (angle of incidence equals angle of reflection), then eventually the ball will enter the "pocket" located at the 60-degree corner of the triangle.

Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Triangles Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Angle Calculation Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Plane Transformations -> Congruence Transformations (Isometries) -> Reflection -

Question

In the plane, a square and a point `P` are given. Prove that it is impossible for the distances from `P` to the vertices of the square to be `1`, `1`, `2`, and `3` centimeters?

Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Triangles Proof and Example -> Proof by Contradiction Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Triangle Inequality