Geometry, Plane Geometry

Plane Geometry concerns figures and shapes on a flat, two-dimensional surface. It covers properties of points, lines, angles, polygons (like triangles and quadrilaterals), and circles. Questions typically involve proofs, constructions, and calculations related to these elements.

Area Calculation Triangles Circles Symmetry Angle Calculation Pythagorean Theorem Triangle Inequality-

Where is the point?

In a convex hexagon ABCDEF, triangles ACE and BDF are congruent and regular. Show that the three segments connecting the midpoints of opposite sides of the hexagon intersect at one point.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Symmetry Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Triangles -> Triangle Congruence Geometry -> Vectors- Gillis Mathematical Olympiad, 2019-2020 Question 3

-

THE CHRISTMAS PUDDING

"Speaking of Christmas puddings," said the host, as he glanced at the imposing delicacy at the other end of the table. "I am reminded of the fact that a friend gave me a new puzzle the other day respecting one. Here it is," he added, diving into his breast pocket.

"'Problem: To find the contents,' I suppose," said the Eton boy.

"No; the proof of that is in the eating. I will read you the conditions."

"'Cut the pudding into two parts, each of exactly the same size and shape, without touching any of the plums. The pudding is to be regarded as a flat disc, not as a sphere.'"

"Why should you regard a Christmas pudding as a disc? And why should any reasonable person ever wish to make such an accurate division?" asked the cynic.

"It is just a puzzle—a problem in dissection." All in turn had a look at the puzzle, but nobody succeeded in solving it. It is a little difficult unless you are acquainted with the principle involved in the making of such puddings, but easy enough when you know how it is done.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Symmetry Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 168

-

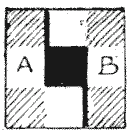

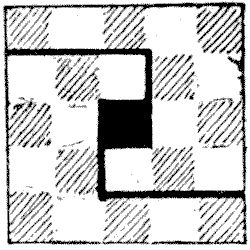

BOARDS WITH AN ODD NUMBER OF SQUARES

We will here consider the question of those boards that contain an odd number of squares. We will suppose that the central square is first cut out, so as to leave an even number of squares for division. Now, it is obvious that a square three by three can only be divided in one way, as shown in Fig. `1`. It will be seen that the pieces A and B are of the same size and shape, and that any other way of cutting would only produce the same shaped pieces, so remember that these variations are not counted as different ways. The puzzle I propose is to cut the board five by five (Fig. `2`) into two pieces of the same size and shape in as many different ways as possible. I have shown in the illustration one way of doing it. How many different ways are there altogether? A piece which when turned over resembles another piece is not considered to be of a different shape.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Symmetry Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Grid Paper Geometry / Lattice Geometry

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Symmetry Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Grid Paper Geometry / Lattice Geometry- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 290

-

THE CIGAR PUZZLE

I once propounded the following puzzle in a London club, and for a considerable period it absorbed the attention of the members. They could make nothing of it, and considered it quite impossible of solution. And yet, as I shall show, the answer is remarkably simple.

Two men are seated at a square-topped table. One places an ordinary cigar (flat at one end, pointed at the other) on the table, then the other does the same, and so on alternately, a condition being that no cigar shall touch another. Which player should succeed in placing the last cigar, assuming that they each will play in the best possible manner? The size of the table top and the size of the cigar are not given, but in order to exclude the ridiculous answer that the table might be so diminutive as only to take one cigar, we will say that the table must not be less than `2` feet square and the cigar not more than `4`½ inches long. With those restrictions you may take any dimensions you like. Of course we assume that all the cigars are exactly alike in every respect. Should the first player, or the second player, win?

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Game Theory Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Symmetry- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 398

-

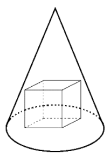

Question

Given a cone (with an axis of symmetry in its center, perpendicular to its base) with a height of 6 and a base that is a circle with radius `sqrt2`. A cube is inscribed within the cone – it rests on the cone's base and all its upper vertices touch the cone. Find the side length of the cube. Justify your answer.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space Algebra -> Equations Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Pythagorean Theorem Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Triangles -> Triangle Similarity

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space Algebra -> Equations Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Pythagorean Theorem Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Triangles -> Triangle Similarity- Gillis Mathematical Olympiad, 2015-2016 Question 2

-

Question

Shlomi has a flat box with a size of `5xx5` centimeters. Shlomi claims that any rectangle that can be stored in this box must have all its sides smaller than 5 centimeters. Is he right?

-

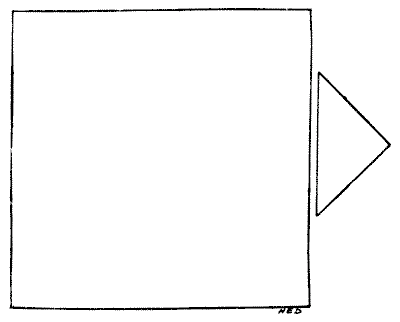

ANOTHER JOINER'S PROBLEM

A joiner had two pieces of wood of the shapes and relative proportions shown in the diagram. He wished to cut them into as few pieces as possible so that they could be fitted together, without waste, to form a perfectly square table-top. How should he have done it? There is no necessity to give measurements, for if the smaller piece (which is half a square) be made a little too large or a little too small it will not affect the method of solution.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Area Calculation Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Pythagorean Theorem Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems

A joiner had two pieces of wood of the shapes and relative proportions shown in the diagram. He wished to cut them into as few pieces as possible so that they could be fitted together, without waste, to form a perfectly square table-top. How should he have done it? There is no necessity to give measurements, for if the smaller piece (which is half a square) be made a little too large or a little too small it will not affect the method of solution.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Area Calculation Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Pythagorean Theorem Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 152

-

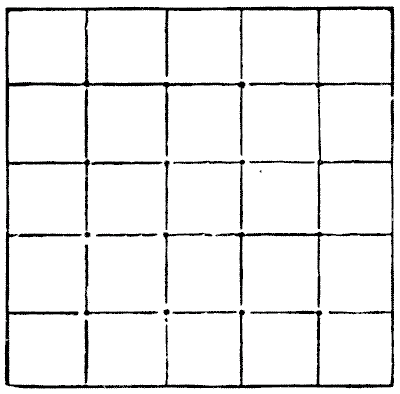

THE SQUARE OF VENEER

The following represents a piece of wood in my possession, `5` in. square. By markings on the surface it is divided into twenty-five square inches. I want to discover a way of cutting this piece of wood into the fewest possible pieces that will fit together and form two perfect squares of different sizes and of known dimensions. But, unfortunately, at every one of the sixteen intersections of the cross lines a small nail has been driven in at some time or other, and my fret-saw will be injured if it comes in contact with any of these. I have therefore to find a method of doing the work that will not necessitate my cutting through any of those sixteen points. How is it to be done? Remember, the exact dimensions of the two squares must be given. Sources:

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 159

-

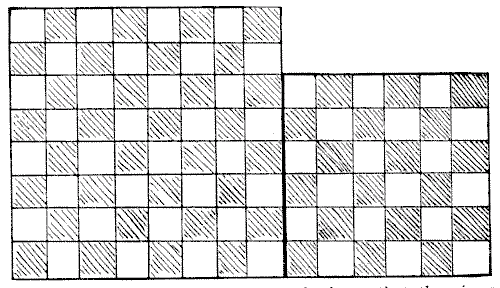

LINOLEUM CUTTING

The diagram herewith represents two separate pieces of linoleum. The chequered pattern is not repeated at the back, so that the pieces cannot be turned over. The puzzle is to cut the two squares into four pieces so that they shall fit together and form one perfect square `10`×`10`, so that the pattern shall properly match, and so that the larger piece shall have as small a portion as possible cut from it.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Area Calculation Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Pythagorean Theorem Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems

The diagram herewith represents two separate pieces of linoleum. The chequered pattern is not repeated at the back, so that the pieces cannot be turned over. The puzzle is to cut the two squares into four pieces so that they shall fit together and form one perfect square `10`×`10`, so that the pattern shall properly match, and so that the larger piece shall have as small a portion as possible cut from it.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Area Calculation Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Pythagorean Theorem Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 176

-

STEALING THE BELL-ROPES

Two men broke into a church tower one night to steal the bell-ropes. The two ropes passed through holes in the wooden ceiling high above them, and they lost no time in climbing to the top. Then one man drew his knife and cut the rope above his head, in consequence of which he fell to the floor and was badly injured. His fellow-thief called out that it served him right for being such a fool. He said that he should have done as he was doing, upon which he cut the rope below the place at which he held on. Then, to his dismay, he found that he was in no better plight, for, after hanging on as long as his strength lasted, he was compelled to let go and fall beside his comrade. Here they were both found the next morning with their limbs broken. How far did they fall? One of the ropes when they found it was just touching the floor, and when you pulled the end to the wall, keeping the rope taut, it touched a point just three inches above the floor, and the wall was four feet from the rope when it hung at rest. How long was the rope from floor to ceiling? Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 179